bloc_article_content

The French-American Treaty of Alliance, 1778

On March 20, Louis XVI formally accepted “the ambassadors of the Thirteen United Provinces”, the first recognition of the United States as a sovereign nation.

When American general Horatio Gates defeated British general John Burgoyne at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, the two sides had been at war for over two years, with the Americans losing almost all of the battles until then. The British army was well supplied with munitions, while at first the Americans had almost none. That changed in 1777, when a large shipment of arms provided by the playwright Pierre Beaumarchais (but but paid for by French and Spanish governments) arrived in New England and gave Gates’s army enough weapons to defeat the British.

France and Spain had been covertly sending small quantities of arms and supplies to the Americans since the war began in 1775. It was part of a long-standing strategy of revanche by France and Spain, both of which were badly defeated by Britain in the Seven Years’ War (1754-1763) but remained allied to each other through the Bourbon Family Compacts. The Americans knew that France and Spain wanted a rematch with Britain, and in fact were depending on them to help win the war. They also knew that neither country would intervene in a civil war, so the Continental Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence to tell king Louis XVI and king Carlos III that America was now a sovereign nation, capable of forming an alliance which together could defeat king George III and his forces.

The French foreign minister Vergennes was certain that an American victory and American independence were in France’s interest, for if Britain won the war – as it seemed almost certain to do – a reconstituted British Empire in North America would be able to prey upon France’s valuable sugar colonies in the Caribbean. He was also convinced that the only way for America to win the war was to form an alliance with France. Vergennes was simply waiting for the right moment to declare that alliance.

Benjamin Franklin had arrived in France at the end of 1776, joining two other American diplomats Silas Deane and Arthur Lee. They hoped to sign a commercial treaty with Versailles. Vergennes avoided discussing this with the American commissioners, because even a commercial treaty would have provoked war with Britain before the French navy was ready and before Spain would commit to the fight. But behind the scenes, he was preparing for an American alliance and drawing up war plans for a combined Bourbon attack on the British. Spain was not yet in a position to join the fight – it had treasure fleets still at sea which were vulnerable to British attack – but Vergennes knew Spain would eventually enter the war as an ally.

The news of the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga arrived in Paris on December 4, 1777. This was the pretext Vergennes had been waiting for in order to forge an alliance with the Americans. He was so prepared for this event that 24 hours after the news of Saratoga arrived, Vergennes had his premier commis Gérard de Rayneval send a letter to the American commissioners requesting a meeting for the following day. A day after that, Gérard began treaty negotiations with the three men. The Americans and French promised to ignore any proposal from Britain that “did not have at its basis entire liberty and independence” for the United States. Gérard, in turn, offered not only the commercial treaty the Americans sought, but also a military treaty of alliance, promising that France would stand with the Americans in the event of war.

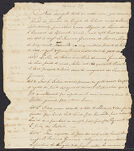

As treaty negotiations continued, Vergennes instructed Gérard to add a separate, secret act inviting Spain to “accede to the said treaties”. On the evening of Friday, February 6, 1778, the final embossed documents – a treaty of amity and commerce, a treaty of military alliance and a secret act -- were ready for signature. The document was signed in Deane’s second-floor apartment at Hôtel de Coislin on the modern Place de la Concorde. When Franklin arrived from his cottage in Passy, Gérard, Deane and Lee were already there, warming by the salon fireplace. The four men compared the English text on the left side of each page with the French text on the right side. Satisfied, Gérard first signed and sealed the documents, followed by Franklin, Deane and Lee, going from left to right. By nine o’clock the ceremony was complete, after which Franklin brought them back to Passy to be copied, while Gérard departed for Versailles.

On March 20, Louis XVI formally accepted “the ambassadors of the Thirteen United Provinces”, the first recognition of the United States as a sovereign nation. Meanwhile copies of the treaty were sent to America aboard the French frigate Sensible, arriving at Falmouth, Maine in April. Couriers brought the copies to the Continental Congress for ratification, and also to George Washington in Valley Forge, who ordered a celebration of the alliance with a feu de joie, an extra ration of rum for the troops, and celebratory toasts of “Long Live the King of France”. One soldier, Henry Brockholst Livingston, wrote to his cousin that “America is at last saved by almost a miracle”, giving voice to the widespread feeling of relief that America was now fighting shoulder-to-shoulder in alliance with France against a common adversary – an alliance that continues to this day.

Published in september 2020

Picture caption : Indépendance des États-Unis