bloc_article_content

The “Western Sea”

From the 16th to the 18th century, explorers, geographers, and the French government were committed to the search for a passage that would facilitate travel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, allowing straightforward access to the treasures of the Asia-Pacific World.

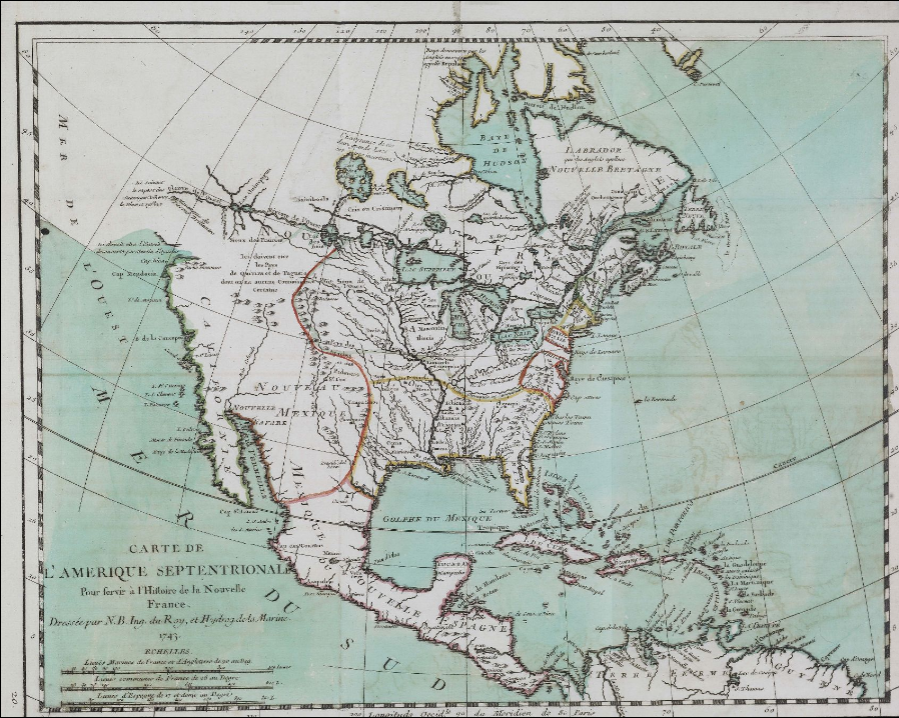

In 1524, Giovanni Verrazano thought he had found an “Eastern Sea” in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, which he imagined extended to the “nearby” coasts of India and China. In the 16th century, both Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain thought they had discovered a deep cross-continental passage along the Saint Lawrence River and the network of Great Lakes. Later, the Mississippi was thought to be the most likely route: in 1672, Jolliet and Marquette were asked to verify whether this river flowed into the “Sea of California.”

The idea of a regional sea north of California was born in the mid-17th century from European misinterpretations of Indigenous reports. Geographers quickly seized upon this hypothetical “Western Sea” and brought it to life on their maps. The Delisle family was at the heart of this geographic illusion. In 1699, the young Guillaume Delisle, who would later become the lead royal geographer and a member of France’s Académie Royale des Sciences, placed a Western Sea on a hand-drawn globe. Interest grew. From 1717 on, the Naval Council and the Regent (Philip II, Duke of Orleans) paid close attention to the matter. The Jesuit Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (1682-1761), who was sent on a three-year mission to Canada in 1720 that took him everywhere from Quebec to New Orleans, conscientiously inquired about the Sea when meeting settlers and Indigenous people. Upon his return to France, he recommended exploring the Sioux country west of Lake Superior, without formally excluding the possibility of a Missouri route to the Western Sea. Around 1730, the political context once again favored expansion; the La Vérendryes began to explore the Great Plains at this time.

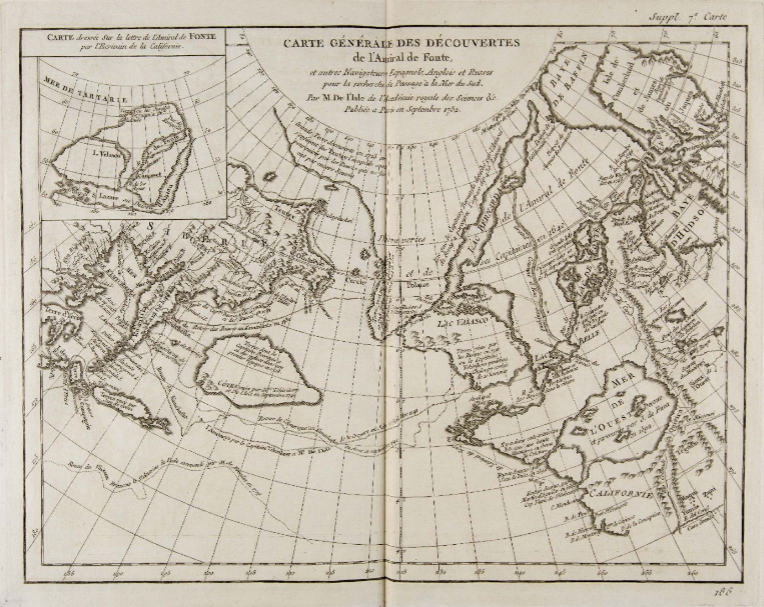

Despite the absence of conclusive findings, the idea of a Western Sea was raised again by Joseph-Nicolas Delisle (1688-1768) and Philippe Buache (1700-1773), both eminent geographers and the brother and son-in-law, respectively, of Guillaume Delisle. In April 1750, Joseph-Nicolas, longtime director of the Saint Petersburg Observatory, presented the findings of Vitus Bering’s voyage before the Académie Royale des Sciences, including a spurious “Letter from Admiral De Fonte,” which mentioned a 1640 voyage of exploration along the North American Pacific coast that suggested the existence of the Western Sea. Despite doubts surrounding the veracity of this document, Philippe Buache used its information to fill in one of the last blanks on the American map, tracing the last bits of the Western Sea left incomplete by Guillaume Delisle. The De Fonte affair divided the French scientific community until 1787, when La Pérouse systematically observed the coasts between Mount St. Elias and Monterey and put a definitive end to this cartographic myth.

Published in may 2021

Réduire l'article ^