bloc_article_content

In the Lands of the Indigenous Peoples in New France (1534-1763)

Starting with Christopher Columbus’s first encounters on the island of Hispaniola, the discursive construction of Indigenous Peoples was at the heart of European travel writings about the New World.

Published in several languages, travel writings functioned as the cornerstone of colonization and structured all knowledge about the Americas. Despite its late settlements in Canada, France features prominently among this vast body of work. Certainly, the way French explorers saw the Indigenous Peoples, as revealed in their narratives and illustrated in the examples offered here, reflects a dated worldview that can be shocking to contemporary eyes.

16th century: first reported contacts

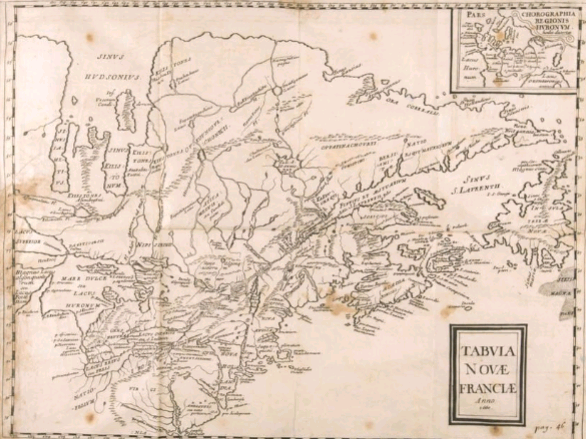

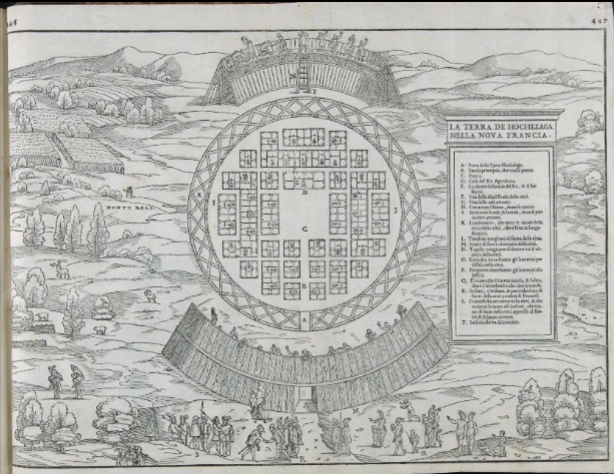

Preceded by anonymous French and Basque cod-fishers, and then by Verrazzano in 1524, Jacques Cartier must have visited the Gulf of Saint Lawrence before obtaining his royal charge in 1534. Implicit in his three Relations, this familiarity with the region comes to the fore in his allusive references to Indigenous populations. Categorized as “sauvages,” “natives of the country,” or else “Canadians,” they are described in a tone that seems factual, almost as if the portrayals are self-evident: “bewildering,” to be sure, but of a fine build; painted, but rarely naked; they fish and hunt with ease. Seeking to befriend his crew, they brought over “skins on poles,” and some traded all of their possessions for metal objects. Cartier developed sufficiently trusting relationships that he even brought several Indigenous people back to France with him (including Donnacona and his two sons in 1536) and, in conformity with diplomatic practices, trained them as interpreters.

An occasional traveller and armchair cosmographer, André Thevet was more verbose in Singularitez de la France Antarctique. While evoking his supposed conversations with Cartier, he praised the beneficence of the “barbarians of this country” and emphasised the diversity of peoples in the Saint Lawrence valley. In sprightly prose, he sketched a flattering portrait of Native Canadians: obedient and “amicable,” obliging and generous, courageous, robust, and valiant, they lived in “community,” were not hairy, and “knew how to cover themselves well with the skins of wild animals.” In sum, while they differed from the French, they were certainly not monsters.

17th century: constitution of a proto-ethnographic knowledge

Tireless traveller, founder of Quebec City, and one-man band in the early years of New France, Samuel de Champlain was also a prolific author. Both in Des Sauvages (1603) and his last Voyages (1632), he emphasized the fragile Franco-Amerindian alliances that served as the foundation of the colony. Anishinaabe (Algonquin) and Innu (Montagnais), Wendat (Huron) and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) -- all of these nations were represented in his writings. The Jesuit Paul Lejeune reported in his Relation for 1633 that, in the spirit of the Council of Trent, Champlain advised one of the local chiefs that: “our boys will marry your daughters, & we shall form a single people.” Thanks to its ambition and reach, Champlain’s work left its mark on the 17th century in Canada, and his adventures echo throughout all writings about New France, missionary and secular alike (Lescarbot, Radisson).

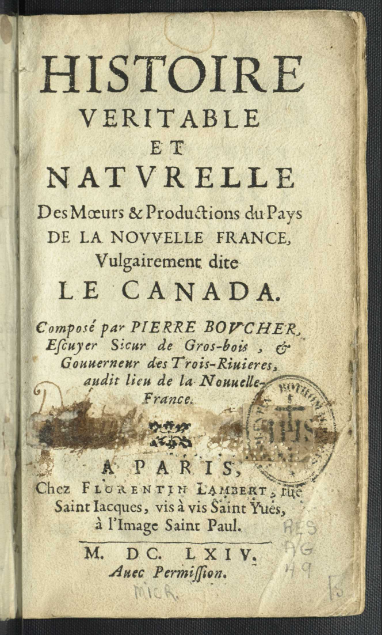

Well-worn though it is, the cliche of unadulterated purity did not inspire the same hopes among all who encountered Indigenous peoples. For Lejeune, a combination of knowledge and patience were the keys to their conversion: “we will instruct the fathers by means of their children,” “who are well brought-up and very kind,” he wrote in 1632, before making a mess of things while wintering among the Innu (Montagnais) two years later. The exceptionally rich observations recorded in thousands of pages of the Jesuit Relations in New France (1632-1672) testify to this intention. Customs, habits, beliefs, languages: nothing eluded them. Adopting a more personal tone, the Recollect Gabriel Sagard admires the great generosity of those whom he calls “my Hurons” in his Grand voyage du pays des Hurons, observing that, in honoring their dead, “they surpassed the piety of Christians.” While most 17th-century priests praised the moral qualities of their Indigenous hosts, the Jesuit Louis Nicolas, like Lafitau after him, additionally relied on them as informants for his Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales (or Codex canadensis) and, in a rarity at the time, rendered some twenty of their portraits in ink.

18th century: from philosophers to allied warriors

Published in The Hague (1702-1703) and widely disseminated, Baron de Lahontan’s viaticum inspired much of the European discourse about America and its inhabitants. While the Nouveaux voyages and Mémoires de l’Amérique septentrionale were widely quoted and plagiarized, from Thomas Corneille to Chateaubriand, or mocked by the historian Charlevoix, it is to Dialogues avec un Sauvage that Lahontan owes his literary reputation. With the figure of Adario, he created a Wendat (Huron) philosopher, a Noble Savage free of “yours or mine, laws, judges or priests.” Variously known as Arlequin Sauvage, Olivette, Jao, Baroco or the Ingenu – Adario and his libertine ideas persisted throughout the century of Enlightenment.

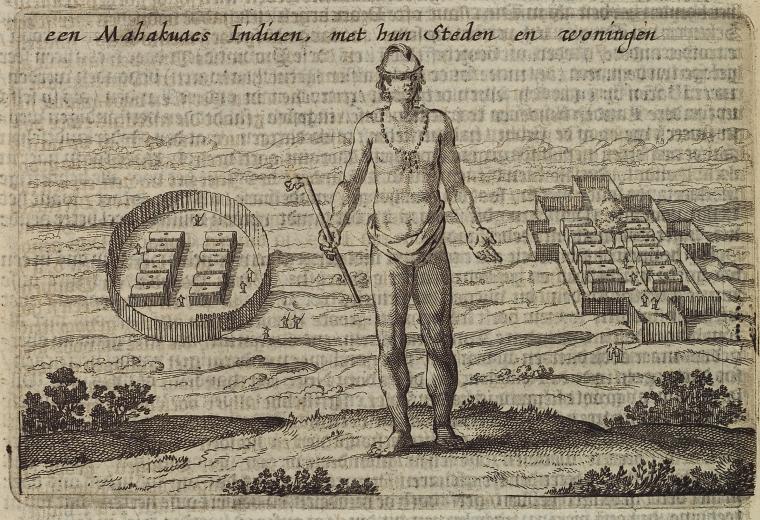

The ubiquity of the Noble Savage in fiction did not diminish travellers’ interest in New France and its Indigenous inhabitants. Drawing upon handwritten memoirs, such as those by the coureur de bois Nicolas Perrot, Bacqueville de La Potherie devoted a large part of his Histoire de l’Amérique septentrionale to Indigenous figures, including an entire volume on the history of the Iroquois up to the Great Peace of Montreal (1701). With their Lettres édifiantes et curieuses (1702-1776), the Jesuits abandoned the apostolic tone of their annual reports. Instead, they convey news from the Louisiana of the Natchez and from the various American theatres of the Seven Years War. Indigenous warriors formed the majority of the coalition troops arrayed against the British, to the dismay of Montcalm and Bougainville. Like most European witnesses to this conflict, they admired these mighty warriors, but abhorred their thirst for liberty and their “war feasts.”

Thus, a voluminous chapter about France in America took shape over the period ranging from Cartier’s travels to the transfer of Canada to Great Britain in 1763. Rich and under-studied, it allows us to grasp the successive representations of the Natives of New France. Tentative and detached at first, they aspired to exhaustivity in the 17th century, before refracting under the glare of the Enlightenment.

Published in may 2021