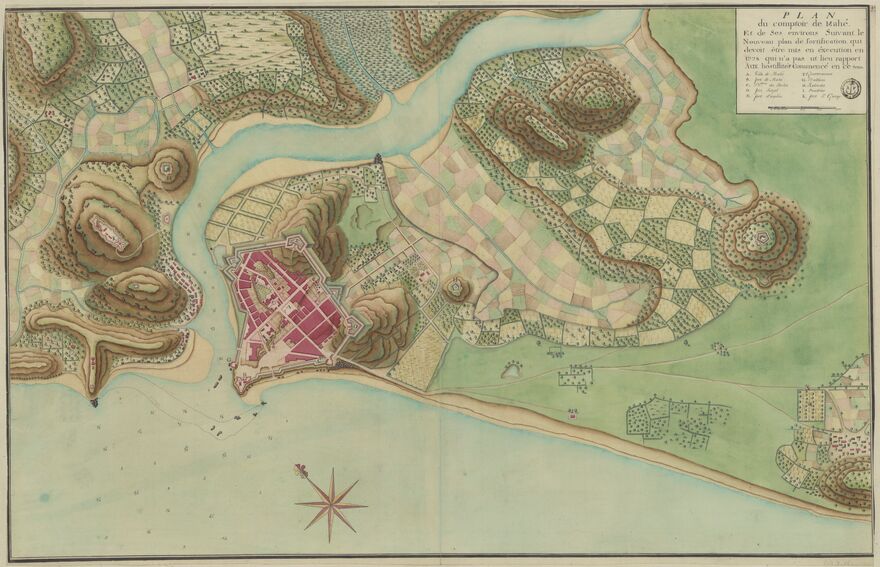

The provisions of the Treaty of Paris of 30 May 1814 pertaining to India were aimed at preventing France’s commercial and political resurgence. The trading posts had been demilitarised and, to facilitate its monitoring of French activities, the East India Company maintained lookout posts within the territory of Pondicherry, making it appear something of a Harlequin. In a bid to ruin France’s trading, it hit the French with double duties on goods entering and leaving the trading posts. The British also violated treaties by refusing to return the right bank of the river in Mahé, because this enabled the French to control salt trading to the interior and spice trading to the sea. Imposed by the British, the treaty of 7 March 1815 banned the French from engaging in lucrative trading in salt and opium, reserving the monopoly here for the EIC. Coupled with these harsh restrictions were the requirements of the ‘Exclusif system’ (système de l’Exclusif), under which the trading posts’ exports were taxed both in France and in the colonies. The famous blue guinée (guinea) cloths of Pondicherry had to be ‘Frenchified’ in Marseille or Bordeaux before being redirected to Senegal, where they were highly sought after. Taxes and tedious detours had one sole aim: to boost industry in mainland France.

France’s only success was its policy on indigenous affairs. Aware of the Indians’ attachment to their religions, habits, customs and castes, the government of Louis XVIII ordered that the Indians, whether they be Christians, Moors or Gentiles, shall be judged according to the laws, habits and customs of their caste – just as they have in the past.’ From then until the cession of 1954, French magistrates recognised polygamy in Pondicherry and polyandry in Mahé, declaring child marriages to be legal and imprisoning babouche-wearing pariahs, said footwear being a privilege reserved for the high castes. This capitulation of the Civil Code to local Indian laws ensured social peace and Franco-Indian harmony.

The Second Empire was a period of economic resurgence. Britain’s, and later also France’s, adoption of free trade had a positive impact in India: as the customs rope strangling the trading posts gradually loosened, Pondicherry resumed its role as a depot and its intra-Asian trade (commerce d’Inde en Inde) with the same prosperity it had enjoyed in years gone by, and goods produced by the trading posts found their natural markets in mainland France and the French colonies. The abolition of slavery similarly benefited Pondicherry and Karikal, where plantation owners from the West Indies, Guyana and Reunion sourced replacement manpower. The period between 1848 and 1885 saw more than 130,000 coolies recruited from British India and taken to these countries on five-year work contracts. One administrator remarked in 1956 that ‘there has been a noticeably improved sense of wellbeing at our establishments in the last six to eight years, and it’s all thanks to the money spent on emigration.’ In 1875, Marseille oil and soap manufacturers began importing large quantities of peanuts from Pondicherry. With Pondicherry’s ever-developing spinning mills and flourishing trade in blue guinée cloth, ‘few other French colonies [at the time] could boast such a booming export business’, said one colony inspector.

Revisiting the revolutionary dogma of assimilation, the Third Republic equipped the trading posts with a full electoral outfit in the form of an MP, senator, departmental council and municipal councils, all elected by universal suffrage. The once so peaceful little colony was immediately gripped by political fervour, with crusaders initially fighting for either the French approach or Indian approach, and then for all-encompassing power in general. 1880 saw French India labelled the ‘land of frauds’. Ten years later, armies of baton-wielding bâtonnistes went head to head.

Published in october 2024

.png)