Guiding light of the symbolist movement in French art, Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) is renowned for painting classical and biblical narratives. Little known is the artist’s fascination with Indian art and its role in his creative process.

Gustave Moreau discovered India during the peak of indophilia in nineteenth-century France, when the study and translation of the Vedas and other scriptures inspired literary works of remarkable poets and writers like Victor Hugo, Lamartine, Balzac and Flaubert. Much like his compatriots, the mysteries surrounding this distant land and the depth of its knowledge system captivated the artist.

Seeking Templates in Indian Art

Artistic traditions from the Indian subcontinent have inspired a number of European artists across centuries. Among them, Gustave Moreau stands out as Indian art becomes a real subject of study throughout his career. He builds a rich repository of formal and iconographical templates from Indian visual sources.

To perfect his understanding of different Indian art forms, Moreau consults several art collections brought back to France by French East India Company officers and adventurers. Preserved at the Bibliothèque Impériale in Paris, just a few kilometres away from Moreau’s residence, these collections were a treasure-trove for any artist seeking authentic sources on India in nineteenth-century Paris.

Moreau’s sketchbook is abound with studies of costumes, ornaments, elephants, falconers, musical instruments and scenes of battles, hunting, and the Mughal court from two collections in particular: History and Drawings of the Gods of Indians or Theogony of the Malabars, a four-volume collection of gauches narrating Hindu mythological episodes painted in seventeenth-century South India and the Gentil Collection, albums of Indo-Persian miniature art collected and commissioned by Jean-Baptiste Gentil, a French military advisor at the court of Awadh in North India.

At the Cabinet des Estampes, he discovers Owen Jones’ Grammar of Ornament (1856), an authority on decorative arts from around the world. Famous nineteenth-century journals like Magasin Pittoresque, to which Moreau had a lifetime subscription, laid the foundation for his deep understanding of Indian culture and art.

Indian Motifs in Moreau’s Paintings

Gustave Moreau’s first oriental work to be exhibited in a salon, La péri (1878) depicts a Persian mythological figure (pari) sitting on a fabulous beast and playing an unknown musical instrument. A Bijapur ragmala print of an Indian woman playing sitar, published in Magasin Pittoresque’s 1838 issue, inspired Moreau’s pari. This print was associated with an advertisement of five dancers and three musicians from India on tour in Paris. The hashia-style outer border of la péri is also an infusion of motifs from Persian and Indian sections from Jones’ Grammar.

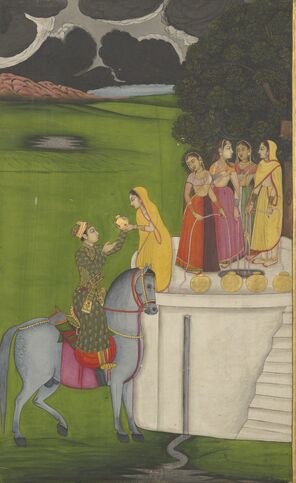

In Poète indien (between 1865-1870), a man covered with ornaments is sitting on a royally-caparisoned horse right next to a young blond woman. She is dressed in a simple purple-coloured gown and standing near a stone column. For this theme, Moreau draws upon a miniature from the Gentil collection—Hindu Woman Offering Water to a Mughal Prince (1760) painted by Anup Chattar around Lucknow or Faizabad. It was also published as a print in Magasin Pittoresque (1856 issue). The theme itself was quite popular among the Mughals and the Rajputs during the eighteenth century.

Moreau takes up the template for composing his Le Christ au jardin des Oliviers (1880) from another provincial Mughal miniature in the Gentil collection: Four Angels Serving Ibrahim Adham, Sultan of Balkh (1760), painted in Murshidabad. The artist also refers to illustrations from Eugène Burnouf’s Inde Française (1827), a collection of lithographed drawings from the French trading posts in India, to sketch different kinds of head gears for his Jupiter et Semelée (1895).

Triomphe d’Alexandre le Grand (1890) embodies the culmination of Moreau’s Indian reverie. Perched on a throne overlooked by the statue of Victory is Alexander the Great. He has just defeated Porus, the king of North India in 326 BC, who is stretching out his arm in a gesture of submission and imploration. In the background, Moreau lays out a dreamed, imagined landscape of India. Here, he mixes up a few references from Hinduism and Buddhism. To paint his signature caparisoned elephants, Moreau referred to the Cernuschi collection and a few photographs he owned. For costumes, he reproduces the studies made after Theogony of the Malabars.

Conclusion

Never having travelled beyond Naples, Gustave Moreau developed impeccable precision and sensibility with which he puts his brush to oriental themes and styles. Drawing upon a collective passion for Indian philosophy, religions and culture, the Parisian artist imbibes Indian art’s visual vocabulary to engage with recurring philosophical debates around universal histories and mythographies.

Publié en janvier 2023

.png)