Founded in 1530, the Collège de France has always remained an establishment for the teaching of Eastern languages. Greek and Hebrew, as biblical languages, were joined by Arabic from the late 16th, and then by Syriac in the 17th century. Turkish and Persian were added to the offering in the second half of the 18th century. The creation of the chair for Sanskrit in 1814 was certainly an early step. It was driven by the movement to institutionalise Oriental studies, which took place at the turn of the 19th century. In India, the British had created the Asiatic Society in Calcutta in 1784, on the initiative of William Jones. This movement was expedited in France by the 1795 opening of the École des Langues Orientales at the Bibliothèque Nationale on Rue de Richelieu, where Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy and Louis-Mathieu Langlès taught Arabic and Persian. It was these two influential figures who managed to convince Louis XVIII to expand the teaching of Eastern languages to include India and China. The decree on the creation of the chairs for Sanskrit and Chinese was signed by the king in November 1814, during the brief period of the First Restoration. The Second Restoration saw the creation of the Société Asiatique in Paris in 1822, while chairs for the teaching of Sanskrit were similarly set up in London, Oxford, Berlin and Bonn.

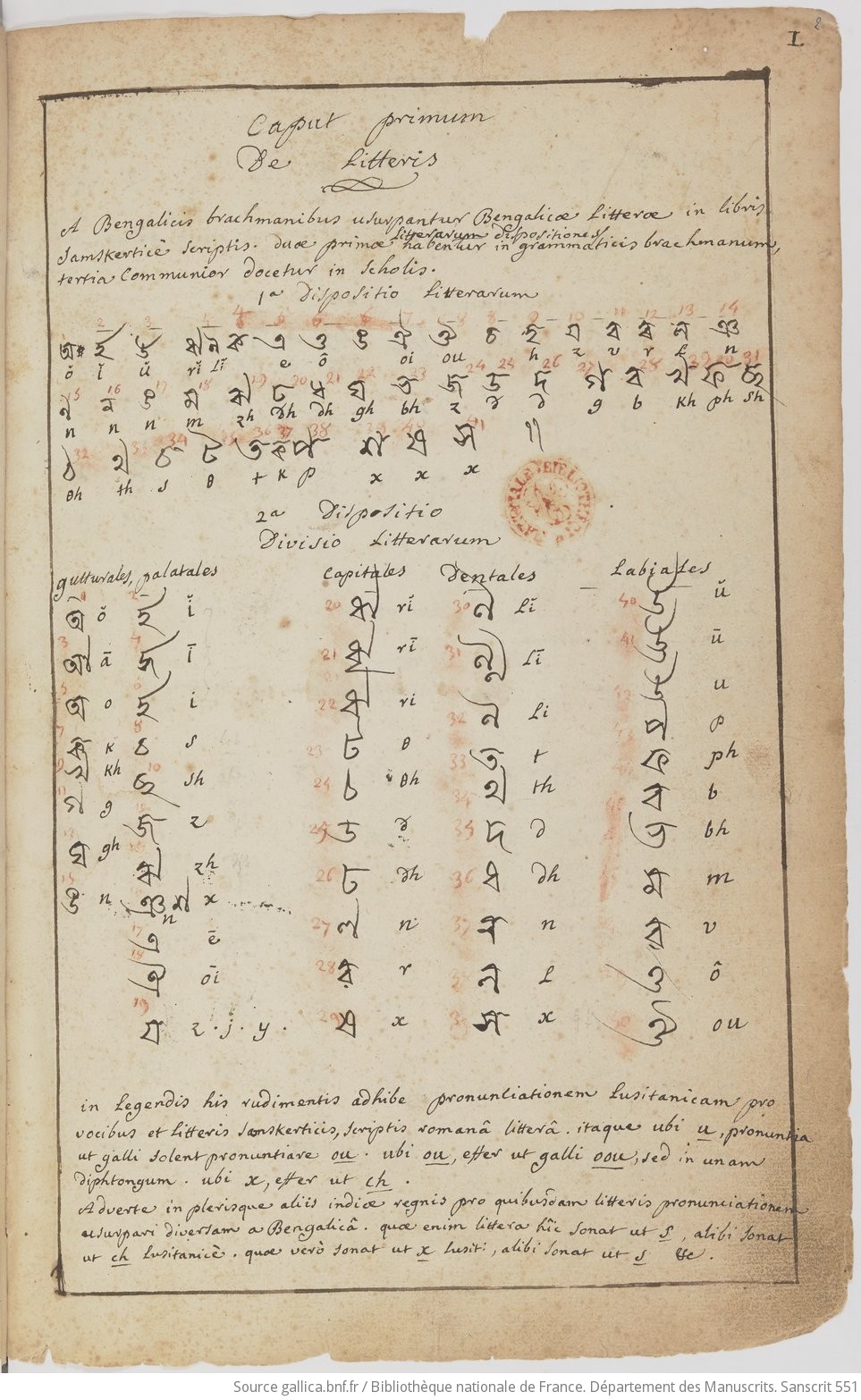

In his Discours d’ouverture du cours de langue et de littérature sanskritedelivered on 16 January 1815, Antoine-Léonard Chézy well and truly 'lifted the veil' off the treasures of Sanskrit literature, comparing them to a 'mysterious sanctuary'. Indeed, before him, there were no French translations of original Sanskrit texts in France. Indian civilisation became known through the pioneering work of Anquetil-Duperron, who had published a Latin translation of the Upaniṣads based on a Persian version. The first translations of Sanskrit texts into European languages came thanks to the British posted in India, namely the likes of William Jones, Charles Wilkins and Henry Thomas Colebrooke. There were thus very few examples for Chézy to draw on in preparing his course. He had learned this scholarly language from the Grammaire sanskrite written by Father Jean-François Pons in Chandernagore in 1730. Using the traditions of the grammarian Bopaveda as his basis, Pons composed his grammar in Latin by writing Sanskrit in Bengali characters. This was incidentally also the script in which Chézy taught Sanskrit, as evidenced by the notes taken by Eugène Burnouf in the Cours de Chézy between 1822 and 1824, while the young scholar was teaching himself the language that would become his entire life.

Sanskrit grammar by Father Jean-François Pons. 1730.

Following Chézy's death in 1832, Eugène Burnouf was appointed to the Collège de France. The son of Latinist Jean-Louis Burnouf, who had also taken Chézy's courses, Eugène was one of the first graduates of the École Nationale des Chartes, established in 1821. A precocious genius with an excellent work ethic, Eugène Burnouf raised the profile of Sanskrit teaching in Paris. Scholars from all over Europe would come and attend his classes, namely Friedrich Max Müller, who was the first to produce a complete edition of the Rigveda texts. In his Discours d’ouverture, Burnouf paid homage to the pioneering work of Chézy and reminded audiences of the linguistic ties between Sanskrit and the scholarly languages of Europe. Comparative linguistics thus provided an occupation for a number of philologists whose knowledge also extended to ancient Iranian languages. Burnouf's scientific papers, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale, demonstrate the breadth of his knowledge and the connections his position as a professor at the Collège de France enabled him to foster, notably with Indian scholars. Among them was the Parsi Manackjee Cursetjee, who played an important role in Burnouf's access to the Avestan texts published in Mumbai.

Burnouf’s early death in 1852 at the age of fifty one left the chair for Sanskrit orphaned. His student Théodore Pavie filled in as a temporary lecturer until Philippe-Édouard Foucaux’s nomination in 1862. Foucaux, a specialist in Tibetan and Sanskrit, shared Chézy’s keen interest in translating Kālidāsa’s Abhijñānaśakuntala or The Recognition of Śakuntalā . In his introduction, he criticised the ‘weakness’ of his predecessor’s translation, while also recognising its vividness and elegance. Foucaux also focused his efforts on the Mahābhārata epic poem, of which he translated a number of chapters. Following his death in 1894, the Collège de France’s chair for Sanskrit took on a new dimension under the direction of Sylvain Lévi, who held it until his death in 1935. Like Burnouf, Lévi was involved in all the orientalist institutions of his time. Director of studies at the École Pratiques des Hautes Études, created in 1868, he served as the president of the Société Asiatique and the Société de Linguistique de Paris, founded in 1864. He also helped found the Institut de Civilisation Indienne. Jules Bloch then held the chair from 1937 to 1941 and again from 1944 to 1951, paying stirring homage to his predecessor in his inaugural lesson entitled Sylvain Lévi et la linguistique indienne. In 1952, this chair, which had been called langue et littérature sanskrite (Sanskrit language and literature) since its inception, became the chair for langues et littératures de l’Inde (languages and literature of India) on the initiative of Jean Filliozat, who held the position until 1978. Filliozat indeed incorporated other scholarly languages of India, namely Tamil, into his teachings. The appointments of André Bareau and, subsequently, Gérard Fussman meant India has remained a permanent fixture at the Collège de France to this day.

Written in july 2024

.png)