India initially committed its texts to memory, as this was seen as the only way to guarantee their preservation and accuracy. So it was that the Vedas were learned by heart using highly elaborate mnemonic processes, imparted by teachers to their pupils. Much of Sanskrit literature was also learned in a similar way. With a hierarchical society founded on deeply entrenched ritual purity, India then inscribed its texts on palm leaves, inventing a particular form of book known as a pothi. Scribes would etch the texts down the length of the leaf, turning the pages from the bottom up. This method endured even after paper arrived in the 13th century.

The first movable-metal-type printing presses were established in South India by the Portuguese Jesuits who had settled in Goa in the second half of the 16th century, and who were followed by the Danish missionaries of Tranquebar (Tharangambadi). But the Indians did not adopt this technology to publish or disseminate their literature. The turning point for printing in India came in Bengal in the late 18th century. Presses were established along the Hooghly River by British missionaries. The first work to contain Bengali type was Nathaniel Brassey Halhed’s A Grammar of the Bengal Language, printed in 1778. Under the aegis of the Baptist Mission, William Carey and Joshua Marshman developed a typographic press in Serampore that would eventually print more than 200,000 texts between 1800 and 1835. These copies produced by the Serampore Mission Press included translations of biblical texts in various Indian languages, such as a Sanskrit translation of the New Testament, as well as initial editions of texts written in Sanskrit and vernacular languages. William Carey also published grammars for Bengali (1805), Marāṭhī (1808), Punjabi (1812), Telugu (1814) and Kannaḍa (1817), together with dictionaries for Marāṭhī and Bengali.

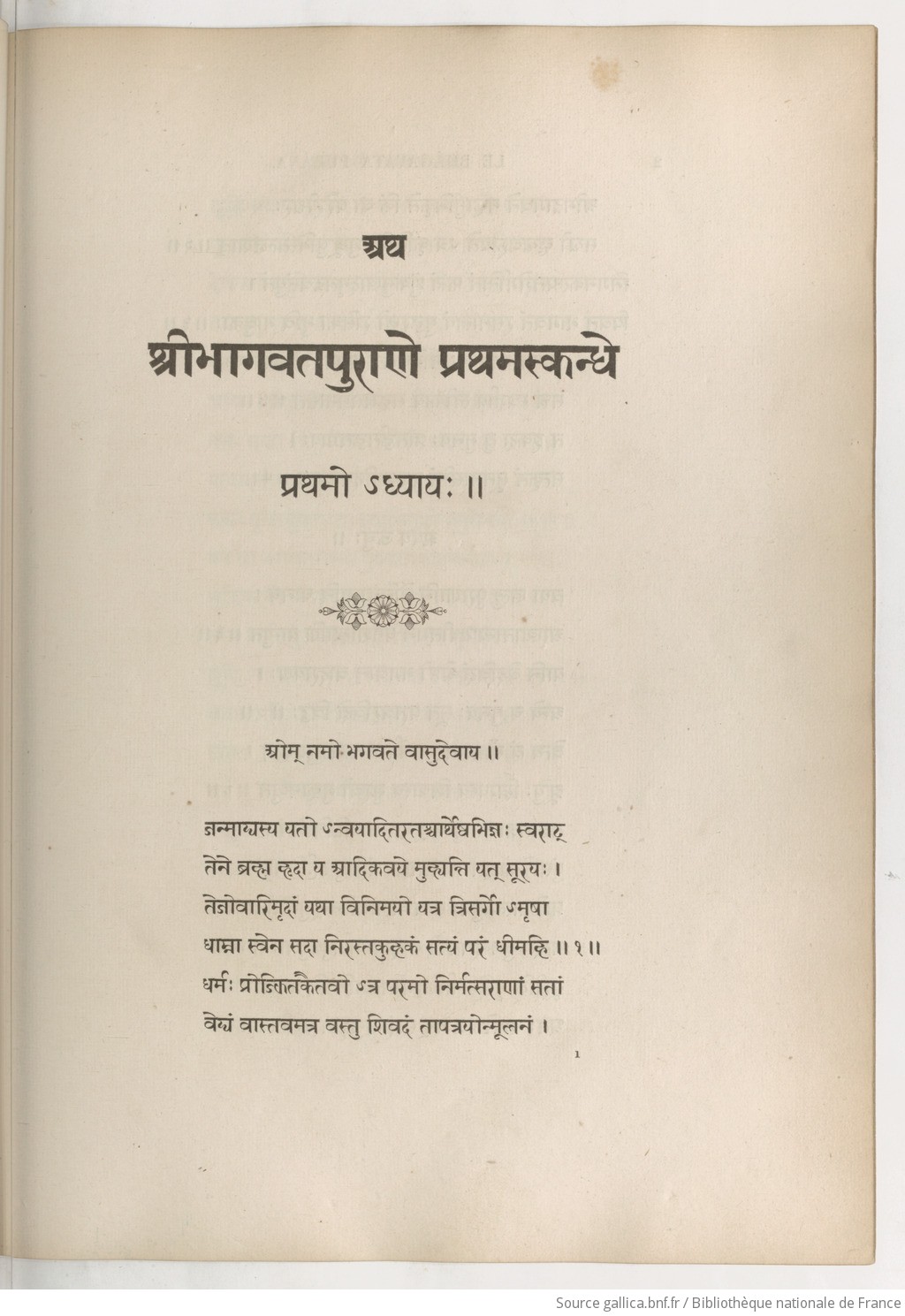

British Sanskritist Charles Wilkins was another figure who played a key role in the region. A trained printer-typographer, he worked with Indian engravers and goldsmiths, most notably Panchanan Karmakar and his nephew Karmakar Manohar. They developed a typeface for the Devanāgarī script, which Wilkins then used to publish his A Grammar of the Sanskrita Language in 1808. Wilkins similarly worked with Bengali scholar Baburam, who founded Baburam Sanskrit Press in Kidderpore, one of India’s first printing houses, operational between 1807 and 1815. The Sanskrit works were printed in Devanāgarī type using the pothi format, thus preserving the reading habits of Indian scholars. In France, Indologist Eugène Burnouf made sure he secured himself these first print editions of Sanskrit texts, as evidenced by the Gītagovinda printed in 1808.

Printing had an equally major impact in Mumbai, which would become the country’s economic centre. The Protestant presses of Serampore served as models for the American Mission Press, which began publishing works on Christian morals in Marāṭhī in 1820. Mumbai also adopted lithographic printing, which prevented the need to develop expensive typeface sets. Publisher and printer Ganapat Krishnaji published a vast number of texts in Sanskrit and Marāṭhī between 1830 and 1850, and lithographic presses were established in Pune and Varanasi to print scholarly editions of Sanskrit texts. Movable-metal-type printing houses continued to advance throughout the second half of the 19th century. Nirnaya Sagar Press in Mumbai, the Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series in Varanasi and the Bibliotheca Indica series in Kolkata saw reference editions of Indian literary texts published and circulated far and wide.

In Europe, Charles Wilkins’ Devanāgarī typeface was used to print Sanskrit texts in London. And in Paris, German scholar August Wilhelm Schlegel teamed up with Vibert, an engraver at the Imprimerie Nationale, to develop a Devanāgarī typeface. Designing the letters involved working off a meticulous copy of the Rāmāyaṇa preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale (Sanscrit 383), sourced in Faizabad by Jean-Baptiste Gentil. This typeface was used at the Imprimerie Nationale throughout the entire 19th century, as evidenced by Eugène Burnouf’s monumental edition of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, whose first volume was released in 1840. Along with a number of other positions, Eugène Burnouf spent a long time working at the Imprimerie Nationale as an ‘orientalist typographer’, developing types for several South Asian and Southeast Asian scripts, namely Tamil script (1832), Burmese script for texts in Pāli (1833), Gujarati script (1838) and Brahmi script (1843), all of which were created in collaboration with different engravers.

The material stakes of the scholarly world were certainly high in the rivalry playing out between the nations. England, which had territorial control, imported the various printing techniques without seeking to develop them. France and Germany, meanwhile, sought to stamp their authority in the philological arena by offering solutions for publishing texts in Indian languages. Under British control until 1947, India used printing to spark a veritable cultural renaissance across the country, ultimately becoming one of the world’s largest publishing markets.

Written in july 2024

.png)