In the modern era, Islam and Christianity are often described as being antagonistic, irreconcilable worlds. If just the voice of ideology had been spoken, then both camps would have remained face to face, each on the borderline. They would have wrapped themselves up in their respective certitudes and the only communication between them would have been confrontational. However, when the facts are examined, this turns out to be untrue and, over the centuries, multiple dissonant voices have made themselves heard. For both parties, the voices of political realism, commercial pragmatism, the appeal of exoticism, technological imitation, orientalist knowledge and philosophical speculation have arisen.

In reality, the European diplomatic game did not stop at the Islamic-Christian frontier. This border was in fact constantly being crossed, in both directions, by all kinds of diplomats, discreet emissaries or ambassadors, bearers of messages, treaties and, occasionally, sumptuous presents. There was another area where the weight of reality led Christians and Muslims to put their ideologies of confrontation to bed to cross pacifically the land and sea borders separating the two worlds: trade.

This wall of antagonism and ignorance has constantly been broken down during the modern era by three categories of knowledge, which are distinct in their objectives, but which have still influenced one another. It is thanks to them that knowledge of the Middle East has reached us.

In the first place, there were travellers. In the 16th century, travel accounts multiplied and, when they were published, were often great successes in the bookstores. The Ottoman Empire or, as it is commonly called, Turkey, was not the sole favoured destination (Persia, India and China, just like the New World, fascinated visitors too). These travellers observed, made enquiries, and were concerned to give their readers as faithful an image as possible of the realities they discovered, with some of them even showing a remarkable open-mindedness.

Another category of communicators with the Middle East can be distinguished from such travellers through their approach. Their main concern was the foundation of Islamic culture in general, the Arabic language and the sources of Islamic scripture, most of all the Quran. Many of them never left in studies to visit the countries where the manuscripts they studied came from. They were the first Orientalists who began to appear in the 15th and 16th centuries; even though this term emerged in English only in about 1779, and in French in 1799, with the Académie Française only recognising the word “Orientalism” in 1838. Their initial intentions were neither Islamophilic nor disinterested. They wanted to get to know Islam better, at a time when the West was being confronted by the power of the Ottoman Emperor (battle of Lepanto in 1571, the siege of Vienna in 1683). They also wanted to learn the Arabic language, just as they had Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac, for the purposes of Biblical exegesis. What is more, they wanted to be able to translate the Holy Scriptures into Arabic, especially for the Eastern Christians who had inhabited these territories for several centuries before the arrival of Islam. Whatever the initial purpose, such knowledge was satisfying and, thus, turned into an end in itself for the learned.

Knowledge of Arabic subsequently became part and parcel of humanist Renaissance culture. In 1539, in France, at the Collège royal (later the Collège de France) Guillaume Postel received the title of royal reader of “Greek, Hebrew and Arabic letters”. While teaching progressed, the essential instruments for work, grammars, dictionaries, and editions of texts, began to appear, not just in Italy and France, but also in Germany, the Netherlands and Britain. Alongside Arabic, knowledge of Islam and Arab history developed considerably. The first European translation of the Quran was published in Venice in 1547; then, in 1647, André du Ryer brought out the first French version of it, L’Alcoran de Mahomet; in 1697, Barthélemy d’Herbelot published his Bibliothèque orientale, an overview of Muslim history.

Among the artisans of this discovery of Arabic-Islamic culture, particular mention must be made of the interpreters (dragomans), the professionals employed by European embassies and consulates, in the “Échelles du Levant”. Trained in the apprenticeship of oriental languages at the school for the “young of languages”, founded in Istanbul at the end of the 17th century, some of them developed into great scholars: Antoine Galland (1646-1715), the translator of the Thousand and One Nights and Jean-François Pétis de la Croix, the author of Mille et un jours in 1732. These dragomans also participated in the research and collection of manuscripts, antiquities and curios which were to enrich the royal as well as private collections, often before entering the national heritage.

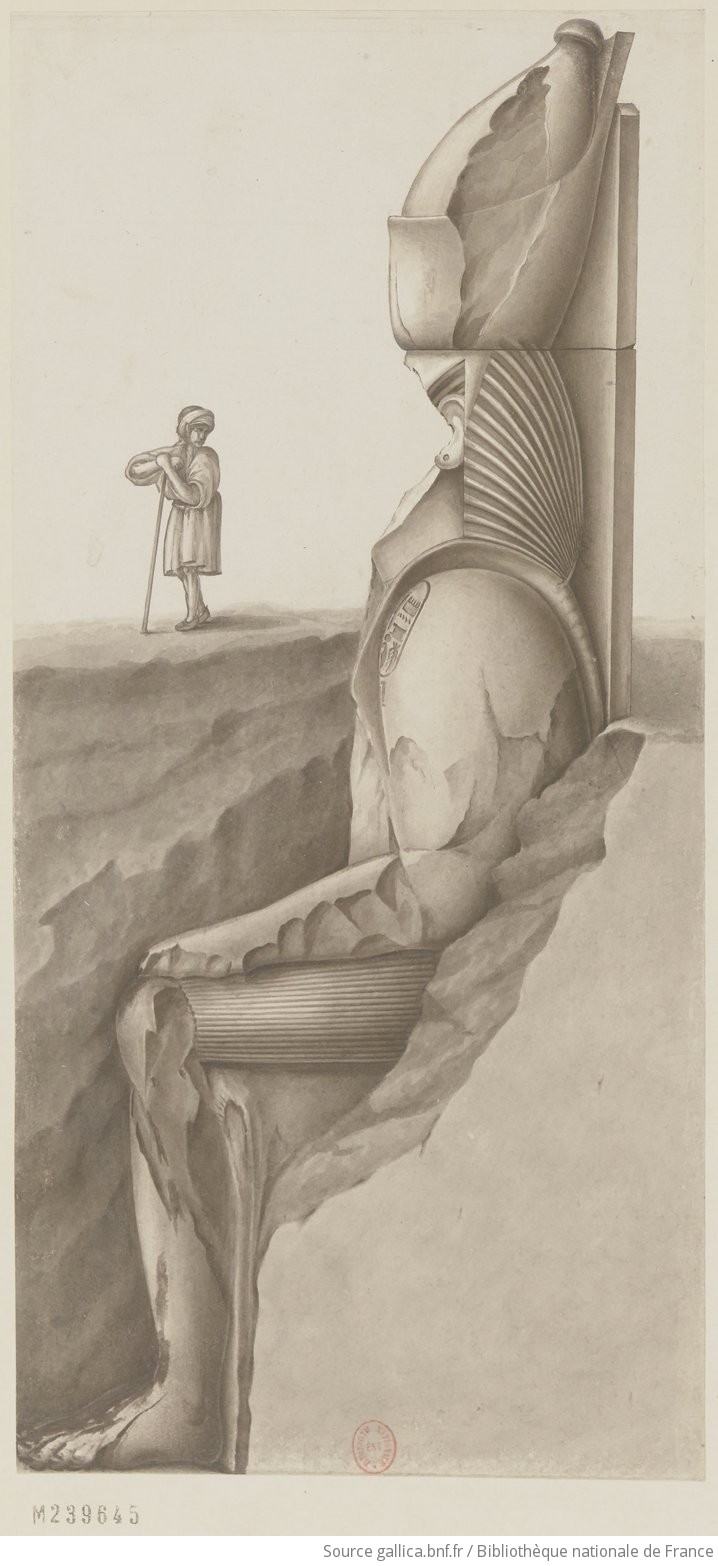

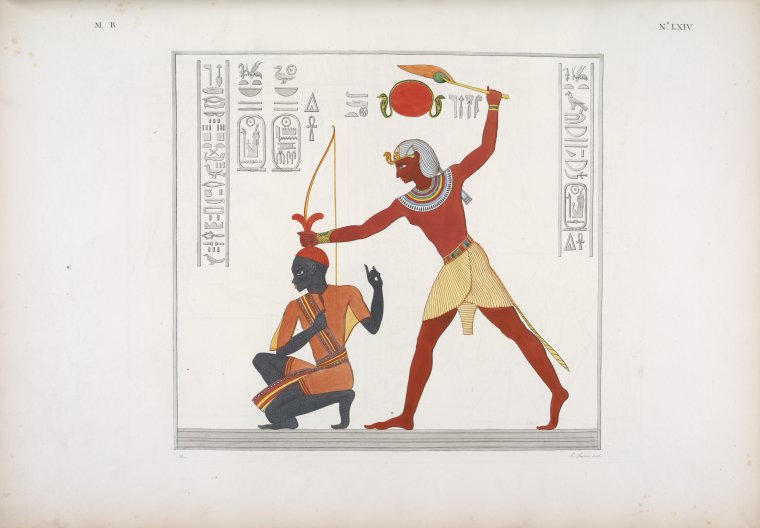

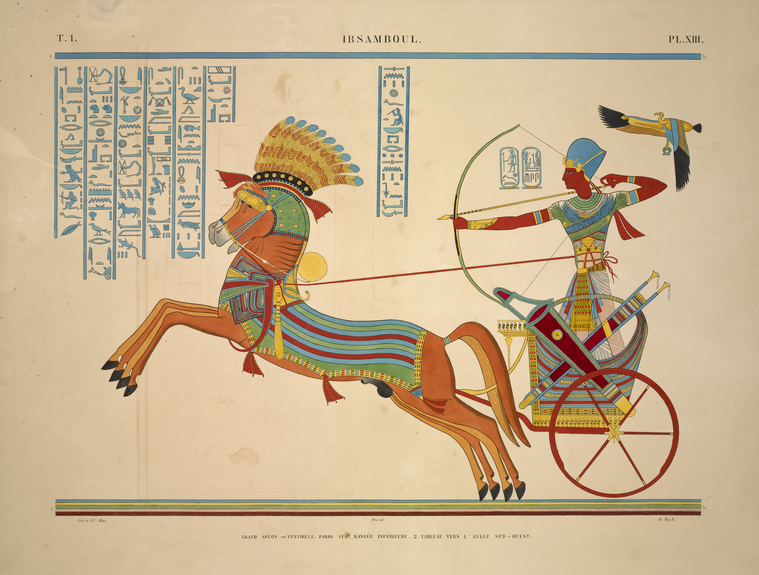

In the 19th century, with Silvestre de Sacy French Orientalism was to conquer the libraries and even, sometimes, become enclosed there, limiting itself to a philological approach to the foundation texts, remaining thus at a distance from the current realities of Islam. But, at the same time, an increasingly large number of artists, musicians, painters, draughtsmen or poets and prose writers, termed Orientalists, composed works which were often called “Oriental” and visited the Middle East. These travels were facilitated by expeditions and archaeological missions, to which were often added colonial conquests.

Progressively, specialised forms of knowledge concerning the oriental world grew up, as well as institutions (schools, libraries, museum collections, journals), while linguistic and other tools were being forged, allowing knowledge of distant worlds to be explored and then deepened.

This entry’s objective was thus to present the history of these forms of knowledge, in all the diversity of their currents of thought and conjunctures.