As the late fruit of humanism and Biblical philology, the traces left by the teaching of the Arabic language in France remain slight.

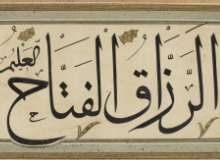

It was in 1538 that François 1st, on founding the Collège des Lecteurs Royaux (the future Collège de France) on the Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève, gave Guillaume Postel the title of “reader” in Greek, Arabic and Hebrew. Between 1538 and 1543, this Orientalist published, just for Arabic, its alphabet in a work devoted to the alphabets of twelve languages, a Grammatica arabica (the first in the West) and a new translation of the first surah, Fatiha, destined for Theodor Bibliander’s edition of the Quran, in Basle in 1543. Subsequently, the occupants of the Arabic chair at the Collège Royal accumulated the responsibility of acting as secretaries-interpreters for the king, for the “Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Tartar” languages, while, as suggested by their name, translating documents for the crown. Among the most famous royal interpreters were François Pétis de la Croix, D’Herbelot, Antoine Galland and Cardonne.

Meanwhile, the embassies in Istanbul and the foreign consulates established throughout the Levant, and other places of exchange in the 16th century, were constantly recruiting interpreters, who were known as terdjümân, truchements, torcimania, dragomans or drogmans. Initially, they were recruited among the non-Muslim subjects of the Sultan: Catholics, Armenians, Orthodox Christians, Maronites, or Jews. But foreign diplomats constantly complained that they were too reliant on their Ottoman masters, or else that they served the highest bidder. This is what led several countries present in Istanbul to open schools for the “young of languages”, so as to have dragomans of their own nationality.

Since 1551, Venice had sent young citizens to study in Istanbul: the Giovanni della lingua. When in turn France decided to open a school, it simply copied the Venetian model, hence the translation as “children of languages” and subsequently “jeunes de langues” (or “young of languages”).

It was Colbert, on the request of the Marseille Chamber of Commerce, who issued a decree on 18th November 1669 for the creation of a school for professional interpreters, “to act as dragomans to France’s ambassadors and consuls in the Orient”. It was initially planned that six “young of languages”, aged from nine to ten, should be sent to the Capuchin monasteries of Istanbul and Izmir. But only the school in Istanbul operated reasonably well. In 1700, because of the lack of satisfactory results, it was decided that these apprentice-interpreters would start their studies at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris, and only be sent to Istanbul at the age of twenty. In 1721, there was a further reform: the school was to be reserved for ten young Frenchmen, either from the Levant, or from the homeland. It was from this period that dates the obligation for people with the function of secretary-interpreter for the king to give lessons at the school for the Young of Languages.

Attached to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1796, this school was to operate until 1873, when it merged with the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes.

The latter, established at the Bibliothèque Nationale, was born under the Convention Nationale, on 10th Germinal, year III (30th March, 1795). In 1873, on the initiative of its president, Charles Schefer, it was transferred to a town house at the corner of Rue des Saints-Pères and Rue de Lille. In 1971, it changed its name to the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO), better known under its nickname “Langues O'”.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Paris became the centre for oriental studies in Europe. It was possible to learn Arabic, Turkish and Persian in three establishments: with a scientific and literary education at the Collège de France where Jean-Jacques-Antoine Caussin de Perceval was an illustrious occupant of the chair of Arabic, and with Abel Pavet de Courteille for Turkish. The apprenticeship of oriental languages for a political and commercial application and use at the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes took place under the supervision of Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy for literary Arabic and Armand-Pierre Caussin de Perceval for colloquial Arabic; Louis Langlès and Etienne Quatremère for Persian; and Amédée Jaubert, Charles Barbier de Meynard and Charles Schefer for Turkish. Furthermore, the government continued to support the “Jeunes de Langues” at the Collège Louis-le-Grand who were destined to become dragomans in the “Echelles du Levant”.

After the scholarly Orientalism of the 19th century had become established, the intellectual world felt the need for a regular publication from a recognised association. Thus, in 1822, the “Société Asiatique” was born. It published a periodical, Journal Asiatique, which still exists today.

The 19th century and the first half of the 20th century marked the zenith of academic Orientalism, at a time when France was a major power, expanding in Africa and Asia, placing under its more or less direct, more or less powerful control a series of colonies, protectorates and mandates.