The military campaign launched by the Directoire in April 1798 was accompanied by a scientific expedition that Bonaparte, at the head of this adventure, wanted to set in the tradition of those led by Louis-Antoine Bougainville, James Cook or Jean-François de la Pérouse. In July, amid the ranks of the Armée d’Orient, the members of the “Commission des Sciences et des Arts” landed on the Alexandrine coast. During the four years of the Egyptian adventure, this heteroclite troop of over a hundred and sixty scholars included men from very varied backgrounds and with different specialities; mostly engineers, they were also antiquarians, architects, astronomers, chemists, mathematicians, doctors or pharmacists, mechanics, musicians, naturalists and mineralogists, draughtsmen, engravers or else sculptors.

Right from the start, they set about undertaking a meticulous and exhaustive study of a country which they thought they already knew, through the accounts of the travellers who had preceded them. These years spent in Egypt allowed for the gathering of a formidable harvest of herbals, papyruses, minerals, stuffed animals, notes, maps, drawings and sketches.

The idea of a collective work arose as soon as they had landed, but only saw the day in November 1799 thanks to General Kléber, who established its main lines: “a gathering to spread instruction, while participating in the erection of a literary monument, worthy of being called French”. After his assassination in June 1800, his successor, General Menou, took up the mantel, while conferring a new dimension to what was now to be entitled “the great work about Egypt”, and placed under the aegis of the Republic.

At the end of 1801, the banks of the Nile were replaced by the Seine, and a new editorial adventure began, entitled La Description de l’Egypte. It was to continue for thirty years.

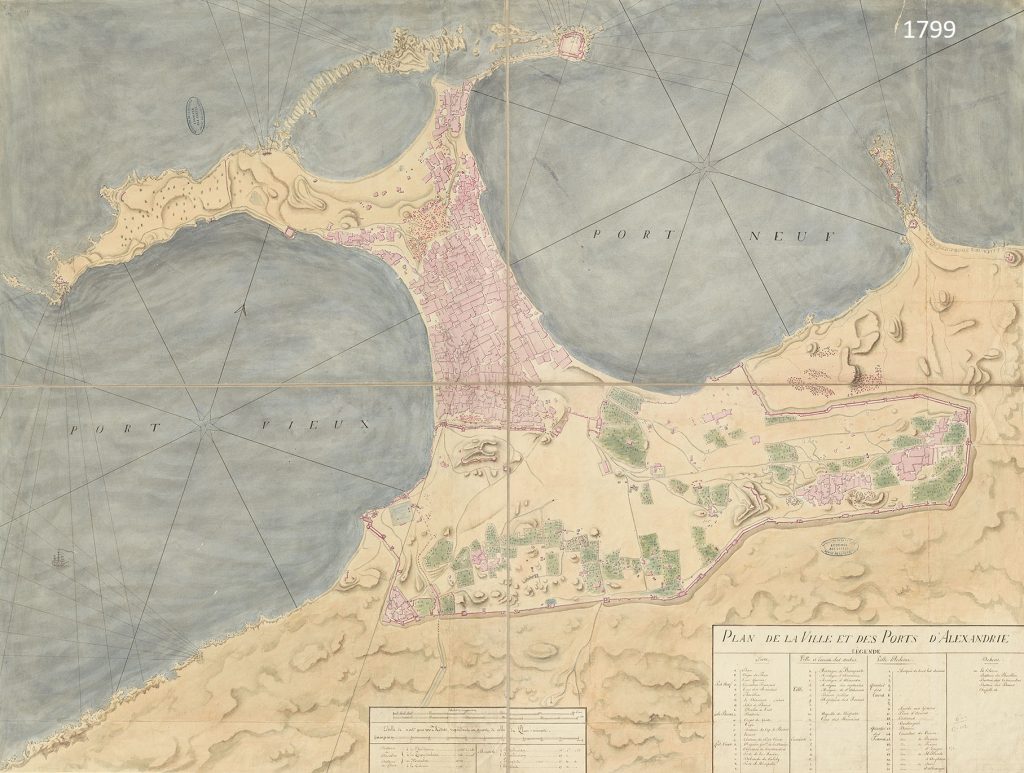

On 6th February 1802, a decree stipulated that all the “memoires, maps, drawings and generally all the results concerning the sciences and arts, obtained during the expedition to Egypt, will be published at the Government’s expense”; the whole was to be divided into four parts: “Antiquities”, “Modern State”, “Natural History” and “Geography” – the latter finally being suppressed for strategic and political reasons. In order to carry out this ambitious enterprise, the Minister of the Interior, Chaptal, appointed a commission called the “Commission d’Egypte”, made up of ten members, including a government commissioner, who was responsible for the publication. This key post was held in turn by Nicolas Conté, Michel-Ange Lancret and Edme François Jomard, the latter carrying out this function for almost a quarter of a century. Twice a month, the Commission d’Egypte examined the articles and plates that had been submitted to it for approval before publication. After having been lodged in Le Louvre, then on rue Doyenné, it joined the Bibliothèque Royale during the Restoration; Jomard, appointed curator in 1828, was, until his death in 1862, in charge of depositing the commission’s archives, and also a large part of the preparatory drawings for the plates of the work, a huge series of over eight hundred original pieces, now preserved at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

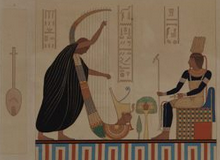

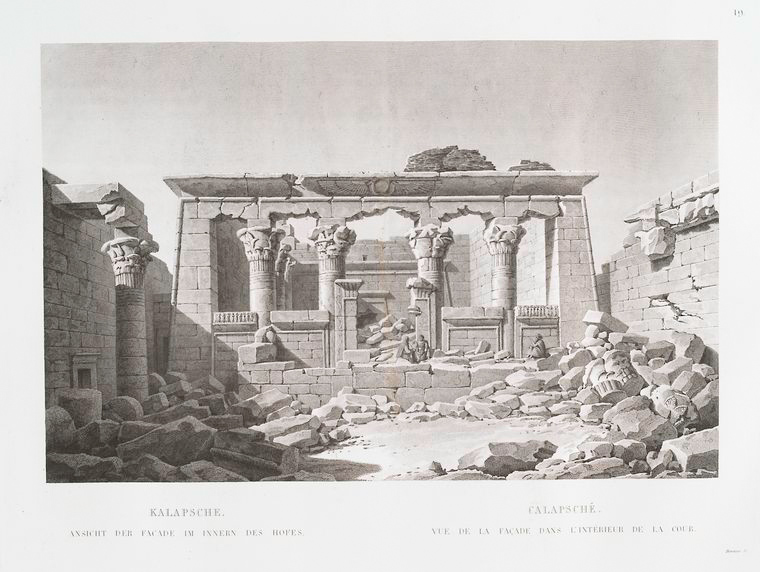

The preponderant place occupied by antiquity in this edition bears witness to the fascination it created. Five of the ten volumes of plates are devoted to this subject. The engineers, draughtsmen and architects of the Commission des Sciences et des Arts did not always succeed in freeing themselves from a mythical vision of Egypt, as can be seen in certain fantastical historical reconstitutions; however, they did render faithfully the monuments they visited. The plans and elevations, the architectural and ornamental elements, all of which are extremely precise, stand as an exceptional collection documenting in an absolutely original way an ancient Egypt that was previously little known.

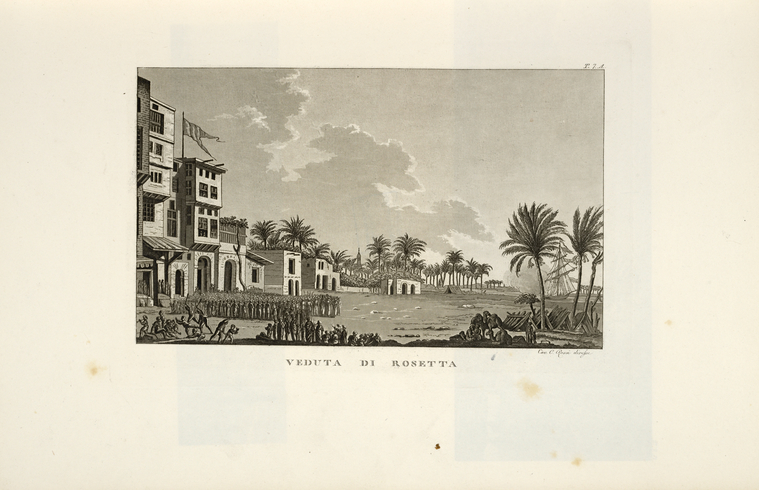

From the Nile Delta to Aswan, thanks to military advances and exploratory missions, these scholars also draw and described modern Egypt, as it was unveiled before their eyes. Following Kléber’s command to “gather all the information required for a knowledge of the modern state of Egypt in terms of its government, laws, civil, religious and domestic customs”, they directed a curious – and graphic – gaze on all aspects of daily life; “Arts and Trades”, “Costumes and Portraits”, “Vases, Furniture and Instruments” thus appear among the sections covering the “Modern State”, with this methodology allowing for all these extremely varied descriptions to appear in the main work. The scholars produced plans, elevations, profiles and sections not just of ancient monuments, but also of the mosques and dwellings they encountered during their travels. While working on perspective, and the play of shadow and light, they sketched landscapes, here with a felucca, there with fishermen. In these plates, they depicted an entire architecture from large Egyptian towns to the smallest village.

Vases, meubles et instruments : instruments orientaux à cordes : dessin / Villoteau del.

The fauna and flora came in for particular attention from the naturalists who, like Etienne Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, had joined the ranks of the expedition. Fish, ibises, palm trees, siricotes and other specimens were scrupulously identified, drawn and even collected, then, after the return to Paris, they acted as models for the plates in the “Natural History” section.

The result of an in-depth investigation whose purpose was to leave no aspect of Egypt unexamined, the Description aimed at providing the most complete and accurate picture ever made of this cradle of the Enlightenment which had fascinated Europe for centuries.

Twenty-eight years were needed for this publishing venture, begun under the Consulate in 1802, to be completed, in 1829, under the July Monarchy. Even this succession of reigns and regimes did not put a stop to the work, which successfully crowned a military campaign, which in many ways had been a failure. As Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire wrote to Cuvier from Cairo in 1799: “We have received the materials for the finest work that a nation has ever undertaken […] Yes, my friend, this work will mean that the Commission des Arts will pardon, in the eyes of posterity, the frivolity with which our nation, so to speak, launched itself into the Orient.”