The were great collections of guide books: Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers (London), Baedeker (Leipzig) and Les Guides-Joanne (published by Librairie Hachette), which are the ancestors of Les Guides-Bleus.

On 11 September 1854, according to a journalist on Le Siècle: “You only visit a country you have already visited or which has been visited for your help. Thus, a guide book is a necessary complement for any traveller, just like a compass is for any sailor”. And during the second half of the 19th century, three major collections dominated the European market: Murray (relying on a large, well-off British clientele), Baedeker (with a broader range of titles in three languages: German, English and French,) and the Guides-Joanne (which in 1919 changed their name to Guides-Bleus).

This French publishing project went back to 1855, when Louis Hachette acquired the travel guides published by Louis Maison and recruited his main collaborator, Adolphe Joanne. He was then appointed as editor in chief of the collection, with the task of revising the existing titles (whose blue percaline covers were kept) and bringing out new numbers. Among the works he brought out were the Guide du voyageur en Orient by Richard and Quétin (1851) and the Guide du voyageur à Constantinople et dans ses environs by Blanchard (1855).

The first Murray’s Handbook for Travellers devoted to the Middle East was Egypt (1847), a classic written by John Gardner Wilkinson, then Turkey (1854), and Syria & Palestine (1858). In the 1870s, Baedeker brought out similar guide books, which were thought to be more practical and handier to use, with a safer selection of hotels and a regular renewal of their large number of itineraries. As for Les Guides-Joanne, they stood out for their numerous volumes devoted to the Orient: around forty of them between 1861 and 1912, updated and completely revised (including eight republications of Léon Rousset’s De Paris à Constantinople).

As soon as he was appointed, Adolphe Joanne set the publishing approach, banning any personal consideration and aiming at a great objectivity. With a view to clarity, he drew up a plan, which was adopted by his son, Paul, who succeeded him after his death in 1881. The guide books opened with general information about the journey and different access routes, followed by a long introduction entitled “Généralités”, which brought together facts gathered from specialists (acknowledged in the preface) about geography, history, architecture, language and the current context (government, religions, populations, customs, etc.). Then came the itineraries. They were thus genuine guide books, with a choice of sites and excursions.

In 1861, Adolphe Joanne and Émile Isambert’s Itinéraire descriptif, historique et archéologique de l’Orient came out. The latter (a doctor, researcher, member of the Société de Géographie) completely revised it as a trilogy: Grèce et Turquie d’Europe (1873), Malte, Égypte, Nubie, Abyssinie, Sinaï (1878) published two years after Isambert’s death, under the direction of his collaborator, the pastor Adrien Chauvet, as well as Syrie, Palestine (1882). For each volume, there were at least three editions, coming out every ten years, with updates of publications, and summaries of the latest findings and archaeological discoveries. All of these volumes were not just travel guides, but genuine works of scholarly compilation, which could become parts of the libraries of armchair tourists.

The Guides-Joanne devoted to the Orient, aimed at a cultivated audience and well-off travellers, were particularly costly: 25 francs on average (those devoted to Europe rarely exceeded 6 francs). This high price can be explained by the cost of producing maps and plans, the size of some of the volumes (over 1,000 pages for the first two volumes of the trilogy), as well as the travel costs of the authors (who were no longer named on the covers after the 1880s).

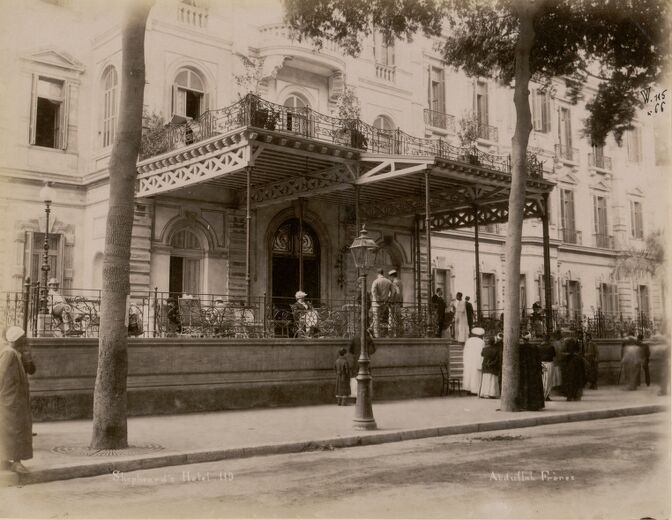

These guide books also had the objective of being useful. The section “Conseils pratiques” informs us about the evolutions of the means of transport (by sea and rail) and the concrete conditions of travelling: spending, currency changes (which were often a genuine head-ache), customs duties and passports, health precautions and lodgings. Such advice also took the form of warnings, in particular concerning the celebrated dragomans, who were direct competitors, and which the Guide-Joanne for De Paris à Constantinople made no bones about calling “off-putting” and “repugnant”, while advising travellers to get out as soon as possible from “their clutches”. More trivial, but still containing a mine of information, advertisements were published in a separate section: medical potions (for the most frequent travel problems), wardrobes and luggage (the abundant amount of which contradicted the advice to travel lightly), and hotels (which were making efforts to meet new comfort norms).