LANGUAGES

On the world map, South Asia is a linguistic region of particular richness and variety. Most of its languages have long histories, often first documented by epigraphists, and many of them are today used by hundreds of millions of speakers. In addition to English and Hindi, the Indian Constitution recognises a further twenty-two languages. Among the linguistic traits common to the majority, the most notable are:

-

The contrast between long and short vowels,

-

The existence of retroflex consonants,

-

A verbal form used specially to express actions occurring prior to those of the main verb,

-

Indirect constructions to express, in particular, sensations or feelings where the grammatical subject is not the person concerned,

-

Specific causative conjugations to indicate that an action has been performed by an intermediary (as in 'to have someone do', 'to have something cleaned'),

-

Verb phrases where one of the two verbs is an auxiliary operating at a semantic level,

-

The use of echo words,

-

An often flexible word order, but with a tendency to follow the dominant pattern of subject – object – verb.

The languages of South Asia can be divided into four families.

Indo-Aryan languages

These form one of the branches of the Indo-European language family, which also includes Latin, Greek, Iranian languages, Slavic languages, Celtic languages and Romance languages.

Old Indo-Aryan

This generic term actually covers all varieties of Sanskrit: Vedic Sanskrit, the most ancient form, used in the Vedas, as well as the classical forms of the language found extensively in literature, and the lingua franca appropriated by all regions and communities.

Middle Indo-Aryan

This encompasses several linguistic varieties and stages of development.

Pali (which literally translates to 'sacred text' as opposed to 'commentary') is the language used in the Buddhist Theravāda Scriptures since the 17th century, initially passed down orally and then also in writing in Ceylon in the 1st century BC. Today, it remains a living language to varying degrees, used by the Buddhists of Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia.

The Prakrits (prākṛta, literally 'natural', 'common') are closely related vernacular languages that were used concurrently with Sanskrit, the language of the elite, for example by women or other characters in ancient Indian theatre. They blossomed into prolific literary and religious languages until the 12th-13th centuries, after which their use waned significantly. The writings of Emperor Ashoka are the oldest verified evidence of this(3rd century BC). While the names of the Prakrits are references to geographic regions, the distinctions between them are still unclear.

|

Śauraseni |

Generally central India (Madhyadeśa) |

Spoken by women and bouffon characters in theatre |

|

Jaina Śauraseni |

Generally central India |

Canonical scriptures of the Digambara Jains |

|

Māgadhī |

Magadha (Bihar) |

Low-class speakers in theatre |

|

Ardhamāgadhī |

Eastern and north-eastern India |

Canonical scriptures of the Śvetāmbara Jains |

|

Māhārāṣṭrī |

Western India |

Lyrical poetry, dramatic verses, epic and narrative poems |

|

Jaina Māhārāṣṭrī |

|

A variety of Māhārāṣṭrī Jain literary texts, commentaries |

The generic term 'apabhraṃśa' (literally 'corruption', 'deviation') encompasses late forms of Prakrit dialects that preceded neo-Indo-Aryan vernacular languages. It is found in mystic Buddhist poems from eastern India and, in particular, in extensive literature produced in Jain communities in India's north and west.

Modern Indo-Aryan languages

Hindi (more than 500 million speakers worldwide) is the national language of independent India, along with English. It is the native language of more than 40% of the Indian subcontinent's population and is also many people's second language, except for certain regions in India's south, where there is a strong anti-Hindi sentiment. The first literary documents in Hindi date back to the 13th century. A wealth of literature also successfully emerged in Hindustani, a form of Hindi heavily influenced by Persian. Standing alongside standard modern Hindi are several other varieties, sustained by a rich literary tradition that has existed since medieval times. These include Braj (in the Agra region) and Avadhi (in the Oudh region), the former being the language of the Krishnaites (Sūrdās, 16th century) and the latter being the predominant language in Tulsīdās' Rāmāyaṇa (16th century). Bhojpuri, spoken widely in the Varanasi region and within the diaspora in Mauritius, and Rajasthani are steeped in oral and folklore traditions, while Maithili is a Hindi dialect from eastern India. Urdu, today spoken by more than seventy-five million people in India (including Kashmir), Pakistan and, to a lesser extent, Nepal and Bangladesh, resulted from a convergence of Indian and Islamic cultures that began in the 13thcentury and the Mughal era. Hindi's sister language, its vocabulary bears the hallmarks of Persian and Arabic.

Punjabi (more than one hundred million speakers) is today spoken in Pakistan and several regions of northern India, including Delhi. While evidence of it dates back to the 12thcentury, it particularly flourished alongside Sikhism and the poems of spiritual master Guru Nanak(15th century), which constitute a central component of the sacred Sikh scripture known as the Ādi Granth.

Eastern Indian languages

These are generally considered to date back to the Māgadhī Prakrit associated with the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, and share a large number of phonetic (a single fricative sh to replace the three sibilants of Sanskrit) and morphological (lack of grammatical genders) traits.

Bengali (or Bangla), spoken by more than 265 million people in Bengal and Bangladesh, emerged as an independent language at the start of the second millennium with mystic Buddhist poems (Caryāpada), and continued to flourish as a language of literature and refined culture.

Oryia or Odia (more than 38 million speakers) originated in the north-east of India around the 10th-11thcenturies. Today, it is primarily spoken in the states of Orissa (Odisa) and Chhattisgarh.

Assamese (more than 15 million speakers) is used in north-eastern India, where it coexists with languages from other families. The earliest records of Assamese can be traced back to the 13th century.

Western Indian languages

These have preserved several typical traits inherited from Sanskrit: three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), sigmatic future etc., and are generally considered to date back to Māhārāṣṭrī Prakrit. They typically developed over three distinct stages: Old, Middle and New.

Gujarati (more than 55 million speakers), spoken in Gujarat, Maharashtra and by a significant diaspora, emerged in the 12th century, as evidenced by religious texts, particularly of the Hindu or Jain variety.

Marathi (more than 84 million speakers), most notably spoken in Maharashtra, is a major literary language, with official records dating back to at least the 12th century in the form of eminent, particularly religious, works. It has been influenced by the neighbouring Dravidian languages.

Konkani (more than seven million speakers), spoken most notably in Goa and along India's west coast, gave rise to, among other things, a vast body of Catholic literature as part of evangelical missions conducted between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Other

Nepali (more than 17 million speakers) is spoken in Nepal, Bhutan and north-eastern India. It is phonetically similar to Hindi, but its morphology and syntax are quite specific, making it an indisputable member of the Indo-Aryan family. The first evidence of it to be confirmed by epigraphists dates back to around the 17th century.

Kashmiri (more than 6,500,000 speakers) is separate from the rest, as it belongs to the Dardic languages that form a branch of the Indo-Aryan group related to Iranian languages. It is spoken in the mountainous regions of north-western India and north-eastern Pakistan.

Sinhala, despite its southerly location, is indeed an Indo-Aryan language. It has a written tradition that dates back to the last few centuries BC, and is today the official language of Sri Lanka, alongside Tamil.

Dravidian languages

Today primarily associated with the southern regions of the Indian subcontinent, these languages once likely spanned the entire territory – as evidenced by the survival of Brahui in Pakistan and the inclusion of Dravidian loan words in the Vedas themselves. India's linguistic history has thrived on ongoing explicit and subtle interactions between Dravidian and Indo-Aryan influences.

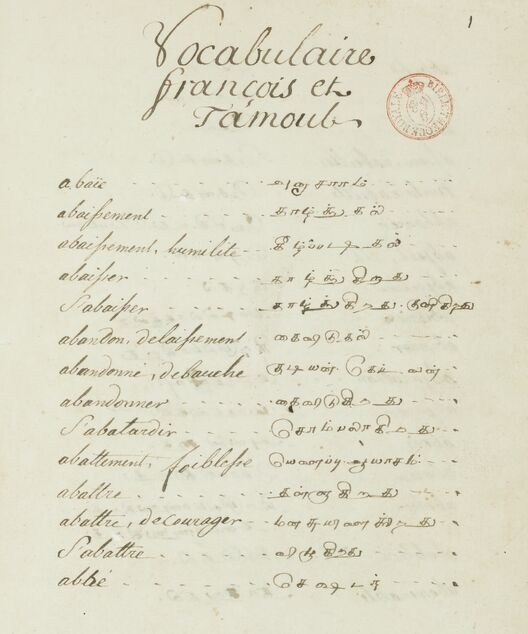

This family, which has no genetic link to any other, encompasses at least twenty-odd languages spoken by more than two hundred and sixty million people, and whose structural similarities have inspired the study of comparative linguistics. Four of these languages boast a long history and have been passed down through the centuries via an abundance of literature and manuscripts: Tamil (more than 78 million speakers), Telugu (more than 86 million speakers), Kannada (more than 44 million speakers) and Malayalam (more than 39 million speakers) are, respectively, the dominant languages in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala today, while Tamil is also the main language of the people of northern Sri Lanka, as well as of numerous diasporas around the world. Tamil, like Sanskrit, is a classical language of ancient India, the first (epigraphical) evidence of which dates back to the 3rd century BC, while the first recorded evidence of Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam can be traced back to around the 6th and 7th centuries. The numerous studies conducted on Tamil (grammar and lexicon) from the 17th century onwards are partly a result of missionary interests. Diglossia, i.e. a marked difference between the written and spoken forms of a language, therefore giving rise to multiple varieties, potentially linked to social status, is a characteristic feature of Tamil, Telugu and Kannada, all of which also have their own regional varieties. Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam all bear varying traces of Tamil and Sanskrit influences across their vocabularies.

Other languages in this family include Tulu, Toda, Badaga, Kodava and Pengo, which all have very rich oral traditions.

Dictionary, French-Tamil, after Beschi. 1800

Austroasiatic languages

Compared with other language families in South Asia, these are spoken by much fewer people and are much less widespread. The Mon-Khmer group particularly includes Khasi (around one million speakers), spoken in Meghalaya, and Nicobarese (around 25,000 speakers), spoken in the Nicobar Islands and comprising several endangered dialects. Munda, represented by several interrelated, non-written languages, is considered something of an indigenous base language of the Indian subcontinent, dating back to prehistoric migrations occurring prior to the arrival of the Aryans. These languages have specific, atypical structures, though there are Indo-Aryan influences apparent in their vocabulary. Munda speakers (around twelve million today) are these days primarily found in the tribal populations of central India (Madhya Pradesh / Maharashtra) or north-east India (Jharkhand, Orissa, Bihar, Bengal), with a few pockets also in Nepal and Bangladesh. In the northern group, Santali is one of the most widely spoken (around 7,500,000 speakers), serving as an official language alongside Mundari (1,400,000) and Ho (1,200,000), while Korwa (34,000) is even less widespread. Books being printed in these languages, which is important to document, is only a recent phenomenon.

Tibeto-Burman languages

These languages are quite confined in their use. Related to Tibetan, they are spoken in Bhutan, Ladakh and Nepal, with the most common being Newar and Tamang. The other main languages in this group are most prevalent in India's north-eastern states (Assam, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Tripura, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim). Two of them, Bodo (1,700,000 speakers) and Meitei, spoken in Assam, are recognised by the Indian Constitution.

SCRIPTS

The Indian subcontinent's most ancient script is that of the pictograms of the Indus civilisation (3000 BC). But the language they represent is still yet to be deciphered. None of the hypotheses proposed have proven convincing.

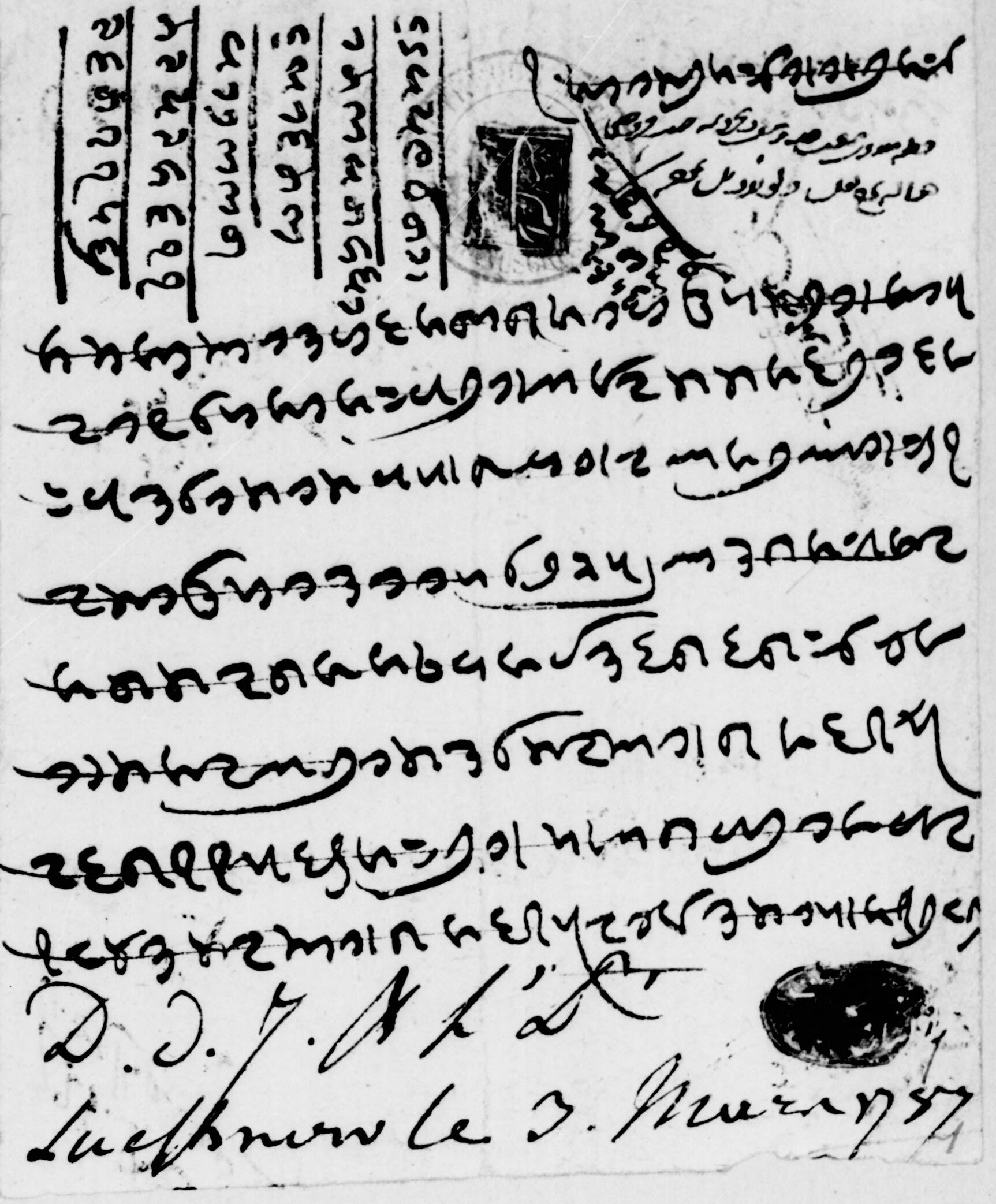

The Kharoṣṭhī script existed for a temporary period between approximately the 3rd century BC and 3rd century AD, limited only to the region of north-west India. It may have been of Aramaic origin, written from right to left, without indicating vowel length. It is associated with the Gāndhārī Prakrit, a Middle Indic language evidenced through rock edicts by Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BC) in the north-west reaches of his empire, in financial documents on wooden tablets found in the oases of central Asia (Niya, 2nd-3rd century) and, in particular, by a rather large number of Buddhist texts, most commonly written on birch bark. Among the most important of these is the Dharmapada 'Verses of the teaching', which initially became known through the 'fragments Dutreuil de Rhins', brought from Central Asia. One section of these can be found at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Pali 715), and gave rise to the foundational studies by E. Senart. Since then, a number of other Buddhist manuscripts written in Kharoṣṭhī script and the Gāndhārī language have been discovered in Pakistan and Afghanistan. They have been preserved at several Western libraries, inspiring and aiding an ever-expanding wave of studies since the 1990s.

The Brāhmī script is the ancestor of most of the scripts used on the Indian subcontinent (India, Nepal, Sri Lanka) and in a number of Southeast Asian countries (Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar). With official records dating back to the 3rd century BC in the form of Ashoka's inscriptions, it evolved, transformed and spread far and wide throughout history. It is written from left to right and forms an alphasyllabic system consistent with the phonetics of Sanskrit and other Indian languages: each consonant contains a short a sound; the vowel sounds associated with consonants are indicated by abbreviated symbols, while isolated vowel sounds have specific symbols. Derived from Brāhmī, the (Deva)nāgarī script gradually began developing between the 6th and 7th centuries, resulting in multiple varieties (Jaina Nāgarī, e.g. Indian 706; Nepali Nāgarī, e.g. Sanskrit 1814). Today, it exists in its modern forms through Hindi, Nepali and Marathi. Related but not identical forms are used in other Indo-Aryan languages (Gujarati: Indian 721, Indian 722; Bengali and Assamese, Oriya, Sinhala). The much more curved scripts of the Dravidian languages (Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam) also ultimately derive from Brāhmī, with records in the Tamil region similarly dating back to ancient times, while the Grantha script is used in southern India to indicate Sanskrit. In Kashmir, the traditional script is Śāradā, which is also derived from Brāhmī and was used to indicate both Sanskrit and Kashmiri. Today, the region's Brahmins continue to use it in religious contexts, together with Nāgarī. It was the Śāradā that gave rise to Gurumukhi, used by the Sikhs and Punjabis.

19th-century Western scholars often endeavoured to formulate, or have Indian intermediaries formulate, tables of these scripts (Sanskrit 1129: five alphabets of India: Devanāgarī, Grantha, Telinga, Sinhala, Tamil; Indian 839 Hindustani alphabet with attempted transcription) and collect documents written in various scripts (Indian 757). Transcription into Latin characters also prompted research and entailed some trial and error before resulting in the standard form that uses diacritic symbols to indicate phonemes specific to Indian languages (macron for long vowels, e.g. ā, ī, ū; subscript dots for retroflex consonants, e.g. ṭ, ḍ, ṇ, etc.).

The Indian scripts do not have a calligraphy per se (unlike Chinese and Arabic), but there are quasi-calligraphic forms that tend to be used in religious works: the Vedas (Sanskrit 320), a holy Jain body of work (Indian 889), while all the stages from cursive script to more intricate forms are also widely documented.

Contrary to certain preconceptions, the Devanāgarī script has not always been the only one to be used to indicate Sanskrit, initially passed down through Brāhmī in all its forms, through the scripts of vernacular languages (e.g. Bengali), as well as, in south India, through Grantha, or, in the north, occasionally even through Persian script.

The case of the Pāli language is particularly unique. It has no script of its own, and can be written in Devanāgarī (most commonly in India), but also using the Sinhala alphabet (Sri Lanka), Khom (Thailand and Cambodia), Tham (north-east Thailand), Khmer (Cambodia), Burmese, Lao or Latin characters (in the West) The plates accompanying the foundational Essay by Burnouf and Lassen (1826) demonstrate this variety, while the alphabetic correspondence tables serve as a means of passing down this knowledge, and there are many examples of this (e.g. (ex. Pali 541 Pāli-Kham-Sinhala syllabary).

While the Arabo-Persian script may not have originated in South Asia, it must still be included here, for it was used to indicate Persian in India during the Mughal and pre-modern eras, as well as Hindi until the early 20th century. Today, it is regularly used to write Urdu, a language spoken in India and Pakistan, in addition to being used by the Muslims of Kashmir and the Punjab. Urdu can, however, also be written using regional language scripts, such as Bengali.

Published in april 2024

.png)