Biography

The child of an illegitimate liaison, Pierre Charles Olloba d’Ochoa was born in Bayonne on 26 February 1816. His mother, Julie Belles, had grown up in a family of merchants – a career path the young man also chose to follow. Throughout his studies in Bordeaux, he was mentored by the Galos family, who were Girondins. He travelled to India on business for the first time in 1835-1836 on behalf of an armament company. His diary, preserved at Paris’ Mazarine Library, reveals little of his stay in South Asia, but does contain several anecdotes from his stop in Sri Lanka. In 1840, he went up to Paris to take Garcin de Tassy’s Hindustani course at the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales. It was there that he met doctor Godefroy Robert, with whom he made plans to conduct a scientific mission to India. Entrusted with handling the geographic and ethnographic side of things, Robert set sail from Bordeaux, travelling to Bombay via the Cape of Good Hope and the French islands of the Indian Ocean. Ochoa left from Marseille, reaching Bombay via Port Said, Suez and the Red Sea – before the existence of the Suez Canal, whose construction was completed in 1869. From Bombay, Robert headed north, fell ill and became embroiled in a long, fruitless mission. Responsible for the literary side of the mission, Ochoa arranged for the collection of manuscripts via Maharashtra, from Nasik and Aurangabad in the north, to Bijapur in the south, in the present-day state of Karnataka. He particularly spent time in Pune and Pandharpur, the latter being home to a deep tradition of devotional Marathi poetry. After falling ill, he was forced to return to France in the autumn of 1844. He died on 2 June 1846 at the age of thirty, without ever being able to bring the results of his mission to fruition.

Collection

The works collected by Charles d’Ochoa were sent to the Bibliothèque Nationale by the French Ministry of Public Education in January 1847. They were loosely catalogued by Eugène Burnouf and Joseph Toussaint Reinaud in a Journal asiatique article as a means of introducing the collection to the academic world. Comprising more than three hundred works, this multilingual compendium paints an accurate picture of a multicultural India. Having a keen interest in poetry and religion, Charles d’Ochoa had focused his efforts on devotional poetry in vernacular languages, particularly Marathi and Hindi. He worked closely with pandits from the Sanskrit College of Pune, and made Viṣṇuśāstrī Bāpaṭa, one of his superiors at this university, his main intermediary. In Pandharpur, he became friends with Garuḍadhvaja, a Vishnuite ascetic, who composed a poem in his honour. And in Bijapur, d’Ochoa became enchanted by Indo-Persian architecture, as evidenced by his diary, preserved at Paris’ Mazarine Library. He sorted the shelves of the palace library and acquired a number of Arabic and Persian manuscripts.

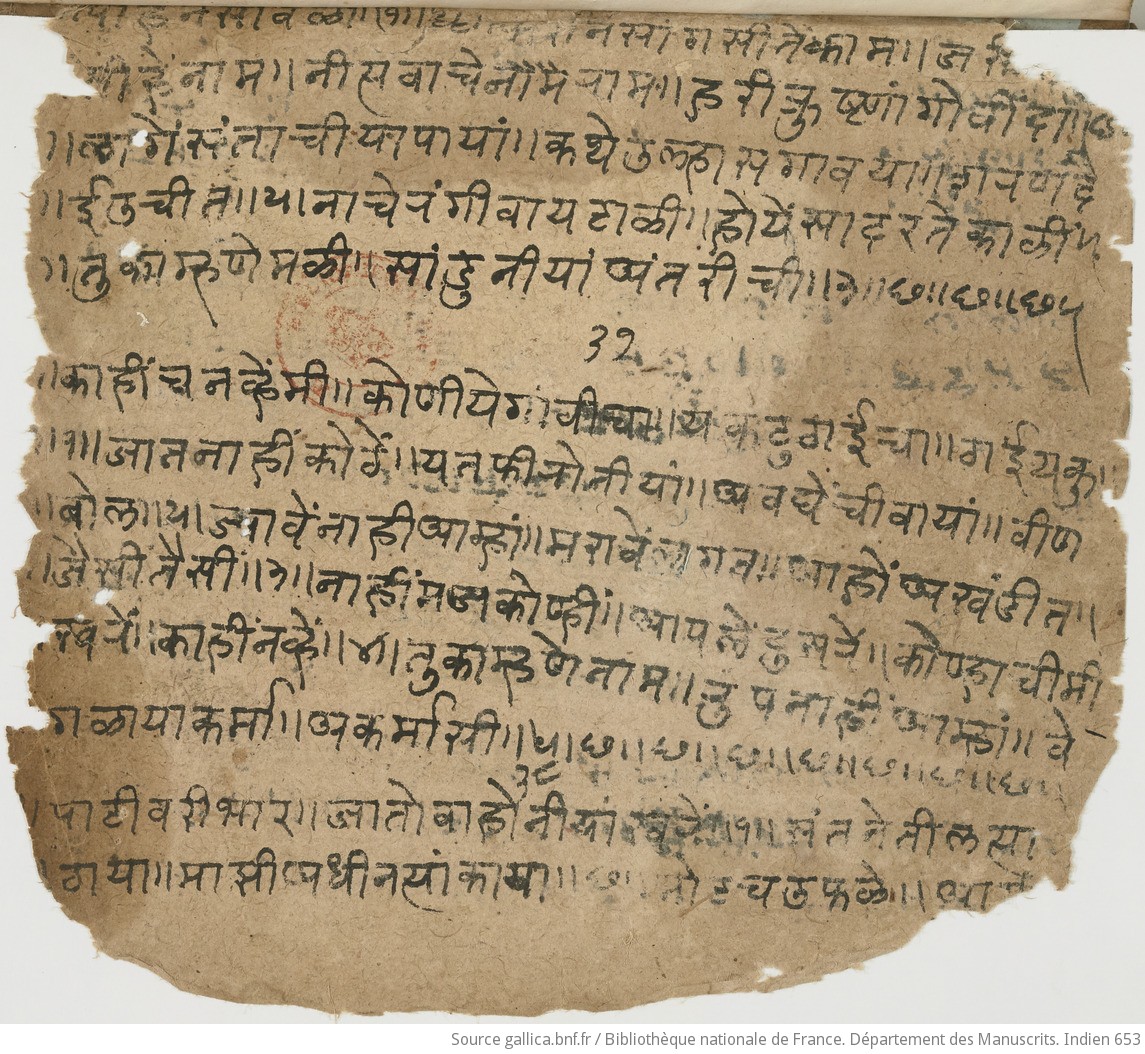

The primary objective of d’Ochoa’s mission was to collect the material needed to write a history of India’s literature. While this excessively ambitious undertaking never eventuated, the materials he collected serve as precious evidence of the efforts he made in what were less than ideal circumstances. The Marathi devotional poems he collected during his stay were the first to find their way into European libraries. They have notably been collated into three duplicate volumes in Pune and Pandharpur. The very first volume (Indian 680) contains lines by Muktābāī, a 13th-century poet who helped establish Marathi literature. The second volume (Indian 681) encompasses the major works of prominent pre-modern poets. The third volume (Indian 682) completes the set, placing a particular focus on the poet Tukārām, who penned a vast body of devotional poems in the 17th century. The latter’s works also feature in a late-18th-century manuscript, a pilgrim’s notebook of sorts, used by the Vārakārī who, to this day, continue to walk all year long, to the sanctuary of the god Viṭhṭhala in Pandharpur. Having a keen interest in non-Brahmanic religious traditions, Charles d’Ochoa also collected Jain texts. He arranged for the reproduction of the Kalpasūtra, the primary text of the Śvetāmbara Jaina, and obtained old copies – in remarkable quality – of other canonical texts, such as the Nāyādhammakahāo. Sikhism was another of his focus areas. He acquired two volumes of Pañj Granthī, collating texts taken from the Ādi Granth and the Dasam Granth. The former was covered in a Punjabi fabric (Indian 693) and contained some forty texts, while the latter, smaller in size (Indian 694), contained around twenty. He also worked in Bombay with a Punjabi merchant by the name of Hajārimal, who helped him decipher the Gurmukhi writing system used in the Punjab, and who copied the opening lines of a poem in old Hindi dedicated to the god Hanūmān (Indian 692) for him.

Œuvres de Tukaram, poète mahratte, 17 century

Published in july 2024

.png)