An abundance of travel narratives from New France, and the consecration of a colonial Canadian canon beyond the realm of fiction, long overshadowed a vast corpus of exoticism. In the early 20th century Gilbert Chinard rediscovered such texts, and explored how their Indigenous characters revealed the imagined America of early modern France.

16th century: the first mentions of Canada in fiction

Shortly after the publication of Jacques Cartier’s Second Voyage (1545), fiction adopted Canada. Far away and mysterious, the place also benefited from the prestige of novelty. Yet, prior to the 18th century, authors exploited New-France above all as an adaptable setting. When Pantagruel in Rabelais’ Quart Livre (1552) discovers the Isle of Medamothi, whose extent “was less large than Canada”, its “Indians” are mentioned only once. As for Marguerite de Navarre, whose 67th tale in her Heptaméron (1558) constitutes the first of the three versions of the legend of Marguerite de Roberval, she first set her story in “the Isle of Canada”, where “local people” lived, then on an island inhabited by wild beasts. Whether it was haunted, as in François de Belleforest’s Histoires tragiques (1572), or situated at a fair distance from a vague “barbarian people” as in André Thevet’s Cosmographie universelle, this isle of Demons remained as hostile as it was supposedly uninhabited.

17th century: a timid arrival of native characters

In Les États et Empires de la Lune (1657), Cyrano de Bergerac lands with splendour near Quebec. In confusion, he addresses" an olive-coloured native", who is naked and fearful, and whose language evokes “a mute's hoarse chirping”. Meanwhile, since the beginning of the century, a few Indigenous people had acquired speaking roles. Les Amours de Pistion et de Fortunie (1601/1606) tells the love story of a French couple in Canada. Inhabited by “Indians”, and more rarely “Barbarians”, this kingdom is governed by the worthy Castio, assisted for many years by a Frenchman, Pistion. Faced by the imminent attack of Acoubar, Fortunie urged Castio to preserve the freedom, religion and honour of his people. After making a solemn promise, this king dies a hero’s death. At the end of the conflict, Pistion is chosen to replace him, Fortunie becomes his queen and the final ceremony includes a thousand dances “in the manner of the country”. Faithful to the novel, Acoubar, ou la loyauté trahie (1606/1611), a tragedy in five acts written in alexandrines by Jacques Du Hamel, lent this plot a more serious tone. Disguising himself as an “Indian”, in a ploy free of any comic effect, Pistion defeats Acoubar.

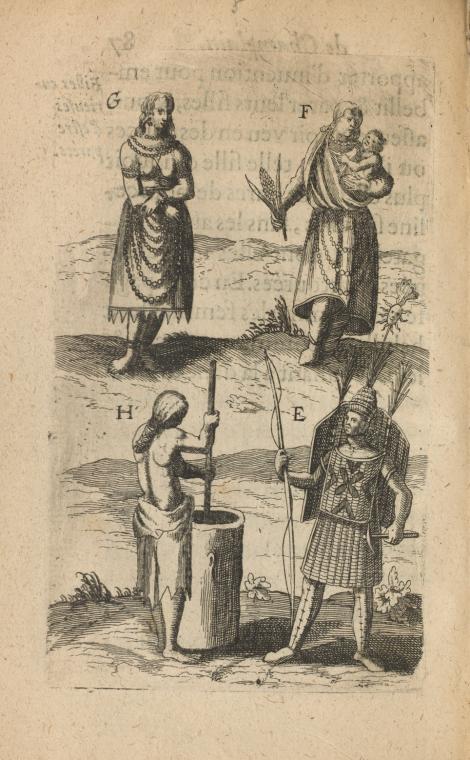

Such colonial conflicts are absent from Marc Lescarbot’s Théâtre de Neptune en la Nouvelle-France. Presented in 1606 at the Port Royal, Acadia in honour of the Sieur de Poutrincourt, it was the first play to by performed in North America. In it, four “Indians” pay homage to Poutrincourt, their “Sagamo” (or captain), by giving him a piece of moose, beaver skins, “matachiaz” and a harpoon. However, despite the thousands of pages published on this subject by travellers, New-France and its inhabitants inspired little fiction, and generated above all fleeting allusions, as in François de Rosset’s Les histoires mémorables et tragiques de ce temps (1614).

18th century: the noble Savage at his height

In his Dialogues avec un Sauvage (1703), Baron de Lahontan crossed rhetorical swords with Adario, a "Huron" who had made reason his credo. Whether debating religion, law, happiness, medicine or marriage, he crushed the Frenchman’s weak arguments. Whether visibly, or in more spectral fashion, the presence of the pair Lahontan-Adario could be felt down to Chateaubriand.

In 1720, Adario appeared at the Saint-Germain Fair in Arlequin roi des Ogres by Lesage, Fuzelier and d’Orneval. He even spoke in Algonquin. The following year, Delisle de La Drevetière presented Arlequin sauvage at Les Comédiens Italiens. The instant and lasting success of this comedy was largely thanks to the repartee of its Indigenous protagonist, who knows nothing about France except its language. Like Adario, he makes skillful use of it, from one scene to the next, returning to passages from Les Dialogues, including this Huron ritual related by Lahontan : “Now then, in my country we present matches to girls: if they blow them out, it is a sign that they want to grant you their favours; if they do not, you have to withdraw”. In a sign of the public’s enthusiasm, "Huron" wisdom reappeared at the Saint-Laurent Fair in La Sauvagesse (1732). Inspired by a true story, Lesage and d’Orneval depicted Olivette, who “appeals even to those to whom she tells a few home truths”. With her, too, lovers blow out a match. Finally, in the libretto by Fuzelier, Rameau has Adario sing and dance in his famous Indes galantes (1735-36). After Le Sauvage en France (M. de Nizas, Metz, 1760), in which Jao embodies a particularly caustic version of Adario, depictions of Indigenous figures in the theatre began to vary. From a moving nobility in Billardon de Sauvigny’s Hirza (1767), to a Voltairian one in Le Huron (1768) by Marmonel, they oscillated between the moral perfection of Zamire (Dumaniant, Le Français en Huronie, 1778/1787), the suppressed cannibalism of Oukéa (Zélamire la Huronne, 178?) and the humanity of Ouzaby (De Launay, Le Français chez les Hurons, 1780). In short, these Adarios inspired in playwrights a range of fairly positive (if stereotyped) characters.

Novels and short stories did not escape from this American exoticism, which went well beyond the “Indians” in Manon Lescaut or the adventitious "Huron" in L’Ingénu. Though limited, the corpus of novels was accompanied by a few short stories. Known for his Gil Blas, Lesage drew on his four Canadian-inspired plays, and on some probable memorials to write Les Aventures de Monsieur Robert Chevalier (1732), most of which takes place on the American continent, including New-France. Seized when very young by the "Iroquois", who adopt him according to their customs, the protagonist sees himself as one of them. When he is returned to his family in Montreal, he immediately leaves on a campaign with Algonquins, who soon regret his conversion to buccaneering. In a parallel tale, Mademoiselle Du Clos makes the most of her forced exile to Canada to create an ideal society with the "Hurons".

In shorter genres, except perhaps for “La nouvelle américaine” (1724) by Madame de Gomez, in which the roles echo travel narratives, Indigenous people become philosophical accessories. On the one hand, Bricaire de La Dixmerie presented “Le Huron réformateur”, in which a formerly enslaved Indigenous person fails in his project to impose pure reason in the East Indies, and “Azakia, anecdotes huronnes”, which tells of how the Baron de Saint-Castin "goes native" and marries an Indigenous woman. On the other hand, in a pathetic register which prefigures Chateaubriand’s nostalgia, the Marquis de Saint-Lambert makes the old man “L’Abénaki” an example of natural kindness betrayed by the English officer whom he had adopted as his son, before drawing up a love triangle in Deux amis, conte iroquois a heart-breaking reflexion about faithfulness.

Over two and a half centuries, Indigenous characters were adapted to literary fashions. From initial, fleeting allusions, they would be glorified as "Noble Savages", before undergoing the torments of a triumphant colonialism, and even dying like Atala, far from her loved ones and completely denatured. Without this enduring discursive imaginary, neither Voltaire, nor Chateaubriand might have chosen Indigenous to defend their ideas.

Published in may 2021

.png)

.png)