The participation of the Ottoman Empire in World Fairs under the reigns of the sultans Abdulmejid I (1839-1861), Abdülaziz (1861-1876) and Abdulmejid II (1876-1909)

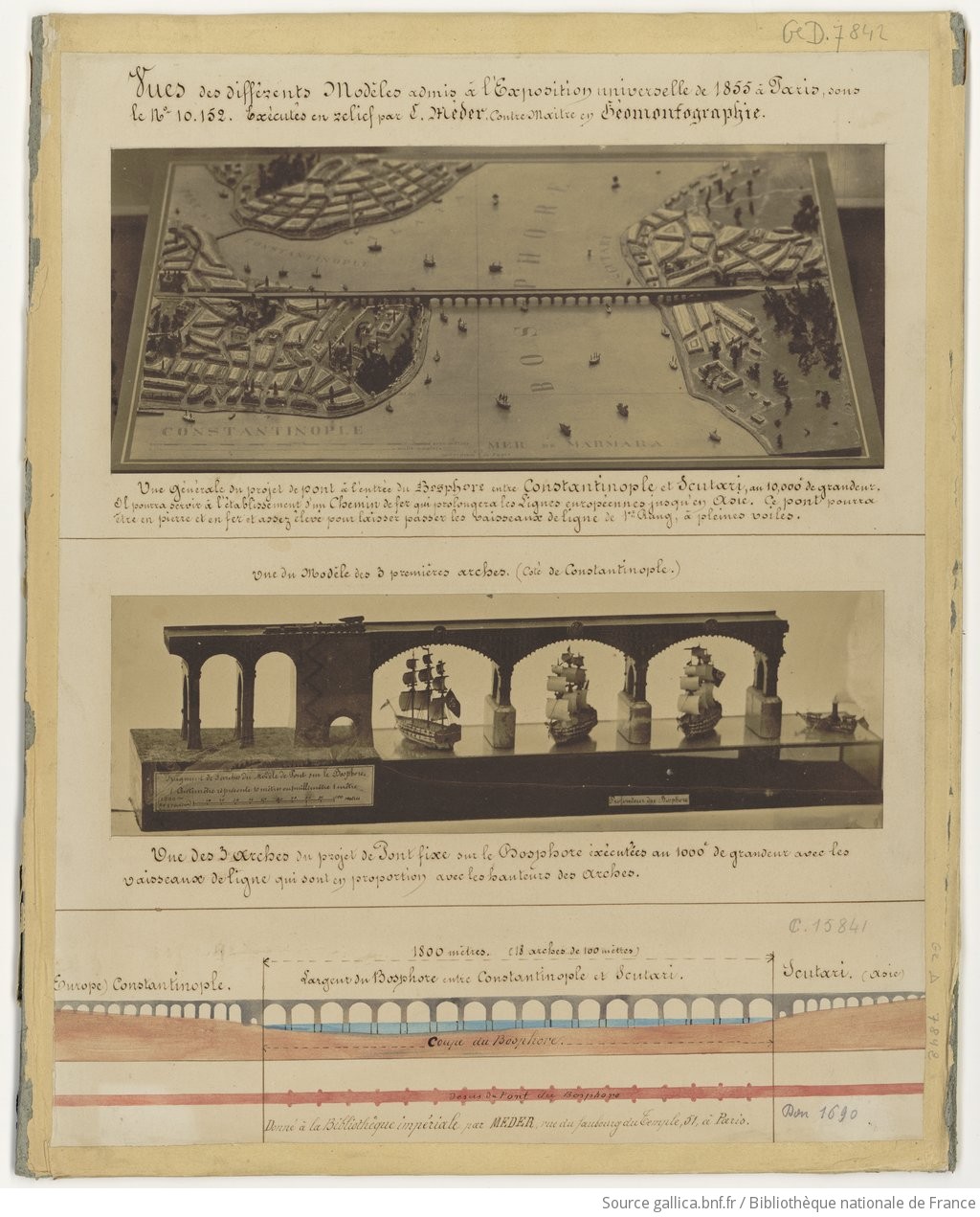

In the midst of the Crimean War, the contribution of the Ottoman Empire to the first World Fair in Paris, in 1855, was restricted to the sending of luxury objects (rugs, musical instruments and damascened weapons) the transportation of which was entrusted to a talented French engineer and photographer, Ernest de Caranza. More surprising, and accepted by the commission, was the project for a bridge over the Bosporus connecting Stamboul to the Asian bank.

Twelve years later, as a guest of Napoleon III, Abdülaziz, the one and only sultan to visit Europe, made the journey. The project manager of the Ottoman pavilion was Léon Parvillée who, among other requests, had restored the monuments of Brousse and decorated the site of the first trade fair organised in Constantinople, in 1863. On the Champ de Mars, he presented a reproduction of the Green Mosque, as well as a residence beside the Bosporus, with walls covered with ceramics, as well as a small-scale model of a traditional Turkish bath. Ismail Pasha, who had just been appointed Khedive, also went to Paris so as to present a splendid “Egyptian Park”, made under the supervision of the Egyptologist Auguste Mariette. The aim was to convey the image of a country attached to its glorious past, while now being distinctly modern.

In 1873, at the Vienna World Fair, two prestigious works appeared to promote the image of the Empire: Architecture ottomane and Les costumes populaires de Turquie. The latter, intended to “provide information about ethnographic and social research”, brought together 74 photographic plates by Pascal Sebah, alongside texts written by Victor Marie de Launay (who had been highly active during the 1867 fair) and Osman Hamdi Bey (a painter who had exhibited his work during the previous show).

Sultan Abdulmejid II, who had accompanied his uncle to the World Fair in Paris, quickly caught on to the point of taking part in such events devoted to progress. In 1878, the Empire was defeated in the Russo-Turkish War then, in 1889, the sultan refused to be associated with the celebration of the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution, so this participation occurred only later, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, in 1893. However, the desire to present the Empire as a state which was an integral part of the civilised world ran up against the expectations of the organisers and the public, who were keen on the exotic and picturesque.

In these huge fairs, set on being as informative as they were entertaining, in Chicago, then in Paris in 1900, visitors could admire fine productions coming from Ottoman industries and crafts, while wandering through bazars full of “local colour” and watching shows (Oriental-style spectacles or else belly-dancing in the Egyptian Palace). Beside the Seine, on Quai des Nations, there stood the impressive Ottoman Palace, a vast amalgamation of different architectural styles, far different from the refinement adopted by Léon Parvillée, thirty-three years earlier.