It was from Britain that the trend for steam baths spread to France during the Second Empire. Apart from their hygienic virtues, French society saw them as being places to socialise.

It was from Britain that the trend for Turkish baths spread to France during the Second Empire. In mid-19th-century Istanbul, David Urquhart, a young Scottish diplomat and philanthropist, took a great interest in the public baths of the Ottoman capital, called hammam in Arabic. He saw in this shared steam bath a way to improve working-class hygiene, while also promoting the social mix in Great Britain. On his return from Istanbul, he set about constructing the first of them in Cork, Ireland, in 1856, a second one in Manchester in 1859, and then in London in 1862; dozens of them were to follow across the country.

They were soon to inspire similar initiatives in France. The first of which was directed by Doctor Charles Despraz, who in 1868 opened in Nice a bath made “after the most perfect plans of numerous Turkish baths in England”. Their use was seen as a leisure activity. But the purpose was also the moral edification of the working classes that used them: “as an honest pleasure to the real detriment of cabarets and other infamous places”. A similar place was also opened in Lyon the next year, while a huge “hammam” offering a full range of thermotherapy opened in Vichy in 1881.

In fact, Turkish baths had already entered the homes of the Parisian elite. La Maison pompéienne which Prince Jérôme Napoléon had built in 1855-1858 on Avenue Montaigne based on plans by Alfred Normand, included a “Turkish bath”. Subsequently, it was for Prince Napoleon that Ingres painted Le Bain turc in 1859, even though the canvas remained in his possession for only a few weeks, before being acquired by the famous Ottoman collector Khalil Bey, known for his taste for erotica. Ingres’ work was purely imaginative, derived from the Oriental letters written by Lady Montagu, published at the end of the 18th century, and reissued on numerous occasions, and in particular her Description of the Women’s Bath in Andrianople.

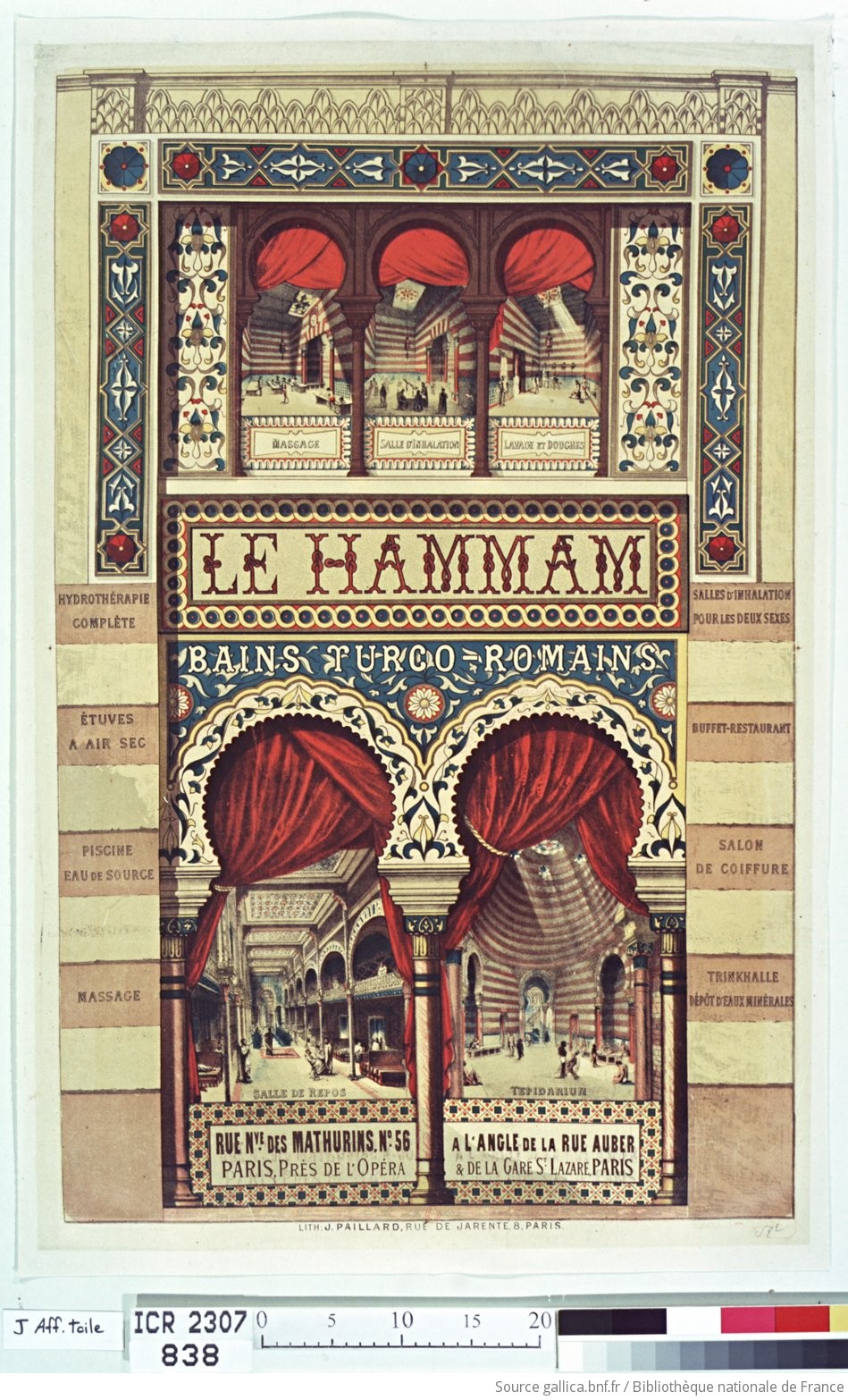

In 1876, two architects, Albert Duclos and William Klein, acquired a property in Paris, at 56 Rue Neuve des Mathurins, where they set up the head office of their agency. On the ground floor of their new investment property, they opened their “Turkish-Roman” baths, which they also managed. Following on from Urquhart, Turkish baths were considered to be the continuation of Roman spas, and the Ottomans were seen as being the conveyers of an ancient practice to modern times; hence the term “Turkish-Roman”. This new installation was based on a strict separation of the sexes. The layout of the baths for the men and for the women were identical, but their entrances were separate. The architects provided the building with a Moorish façade, which can still be seen today at 18 rue des Mathurins, even if nothing of the original interiors now remains, having long since been converted into business premises.

Le Hammam : bains turco-romains, rue Neuve des Mathurins, n°56. 1876

Le Hammam, or Turkish-Roman baths, in the new western quarters of Paris soon became a fashionable meeting point. Ferdinand de Lesseps set up his office there in 1880. “This delicious Moorish palace brings together all the refinements of elegance and comfort” as the press stated during the Exposition Universelle of 1878. Apart from their hygienic virtues, it was affirmed that Turkish baths provided the opportunity for “bodily relaxation”, as well as a “recreation of the mind”. They were also, and above all, a great place to socialise. Such prominent figures as Baron Haussmann, Gambetta, the Dukes of Aumale and Montpensier, Baron Rothschild, Prince Napoleon, Count Potocki, or Baron Seillière were regular clients. Nasser-al-Din Shah, the Emperor of Iran, was a visitor, as was the Emperor of Brazil, who commissioned a photograph from Félix Nadar. This is all very distant from the philanthropic and reformist spirit that had presided over the promotion of Turkish baths in Europe.

In 1926, a Turkish bath was included in the newly built complex of the Paris Mosque. During the decade after May 1968, it became one of the focal points of the capital’s militant feminism, until its public became more varied.