“Grace avenges itself on our science”: thus did Delacroix, in his Moroccan notes of 1832, deplore the mediocre appearance of Europeans, compared to that of the populations he was discovering, draped in their ample, ancient garments.

As can be seen in the numerous albums and collections devoted to them, travellers’ admiring curiosity about Oriental costumes is old and long-lasting; it of course expresses a certain taste for the picturesque, but it also reflects a way of knowing foreigners and their history, which shifts towards a nostalgic perception before evolving into a more ethnographic approach.

The famous portrait of Sultan Mehmed II by Gentile Bellini (1480) is an early instance of the interest of Europe in depictions of Ottoman scenes. This interest grew with the change in the image of the Turks, especially after the failure of the Siege of Vienna in 1683. A fascination mingled with concern then gave way to a curiosity which was to blossom into the vogue for “Turqueries” in the 18th century, due in part to the success of the tales of the Thousand and One Nights, as translated by Antoine Galland (1704). It was during this period that there appeared the Recueil de Cent estampes représentant différentes nations du Levant, published in 1714 on the instigation of Charles de Ferriol, the ambassador to the Sublime Porte. The plates were inspired by Jean-Baptiste Van Mour’s canvases, “painted after nature”, in 1707 and 1708. “Nothing arouses the reader’s curiosity more than garments from different nations, who all seem to go about dressing themselves in such a way as to be distinct from their neighbours”: there follows a parade of the entourage of the Great Lord, military representatives, figures of women spinning, bathing, embroidering, or making music, representatives of the Ottoman Empire, accompanied by an “explanation”, whose comments are sometimes not particularly empathic. But the variety and precision of these plates attracted the interest of such European painters as Watteau, Boucher or Gian Antonio Guardi. It was in this spirit that the collection of “dessins originaux de costumes turcs” was produced during the reign of Selim III (1789-1807), in which can be found characters from the Sultan’s retinue.

A different atmosphere presides over André Dutertre’s drawings (1753-1852), who was chosen as the draughtsman who accompanied the Expedition to Egypt in 1798. Known for having made portraits of its members, he also produced a large series of scenes which were published in La Description de l’Egypte. The BnF collection is made up of pencil drawings and more elaborate pastels, depicting with attention and sympathy figures of Egyptian men and women, who appeared in the “Modern State” section. The quality of these drawings and their freedom of spirit sometimes bring to mind the future sketches of Delacroix.

Curiosity about the “modern” country can also be seen in Louis Dupré (1789-1837), a pupil of David, who discovered Greece in 1819. His Voyage à Athènes et à Constantinople, published in several instalments starting in 1825, is presented as a “collection” of portraits, scenes, and Greek and Ottoman costumes, accompanied by a narrative. While the picturesque nature of these lithographs is never sacrificed, associating as they do figures with precise views of such sites as Ioannina or Meteora, the book plunges the reader into the heart of modern Greek history, on the eve of the 1821 insurrection. Dupré’s work is one of the sources of the Philhellenic movement, stimulating the inspiration of painters with figures of Ali Pasha on Lake Butrint, or the proud “Pallikares” of the Mountains of Epirus.

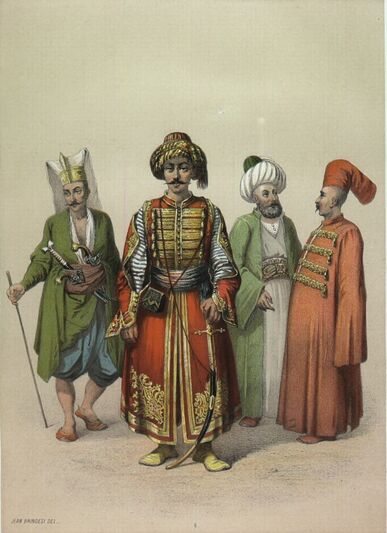

However, the 1829 Reforms (Tanzimat) of Sultan Mahmud struck a heavy blow against the picturesque, by replacing turbans and long robes with the fez and so-called Stamboul uniform. “A retrospective cloakroom of the old Turkish empire”, “an herbal” of its “former nationality”, in the words of Théophile Gautier who visited it, the Museum of Ancient Turkish Costumes (Elbise-i Atika) opened in Constantinople in 1852 on the Hippodrome. It contains models dressed in costumes from the distant past, in particular the Janissaries, a corps abolished in 1826. Jean Brindesi (1826-1888), an Italian painter born in Constantinople, presented this gallery in a volume: Elbicei Atika. Musée des anciens costumes turcs de Constantinople (1855).

Far from these colourful reconstitutions, photography was to introduce a very different approach in the second half of the 19th century. This can be seen in the two views of Alexandria, taken by Gustave Le Gray when he arrived in Egypt (1861-1862): Manœuvres et Maçons depict without artifice everyday scenes in a freer, more realistic way. In the same series, in a visiting-card format, a gallery of figures was made in the more classic genre of the ethnographic portrait, in the almost bare setting of a studio. This genre also lies behind the publishing project of Costumes populaires de la Turquie on the occasion of the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair. Produced by Victor-Marie Launay and Osman Hamdi Bey, and destined to play a leading role in the cultural life of Turkey, this work brought together photographs by Pascal Sebah, in a uniformly sober environment. The attention is focused on the details of the clothes, precisely commented on, in what is already a heritage approach: “Costumes, by becoming adapted to particular requirements, climatic necessities, and the customs of each country, provide ethnographic and social studies with an inexhaustible source of solid information and a potent interest.”