From his childhood reading to an investigation of the Levant, the itinerary of Barrès was placed under the sign of the Orient, mingling poetic dreams and a spiritual quest. Barrès was the last French writer to have been to the Ottoman Empire before the disturbances of the Great War.

Maurice Barrès (1862-1923), the French writer and politician, elected to the Académie Française in 1906, the author of novels and collections of travel impressions, associated his taste for the Orient with the reading by his mother of Walter Scott’s The Talisman, dealing with Richard the Lionheart in Palestine: “This reading, these words from the East and this generous chivalry, and above all that voice became spread out over the world, specifying and nuancing everything I looked at insistently”. “I was born to love Asia, to such an extent that, as a child, I breathed it in, in a garden in Lorraine […],” he added, placing the land of his birth in “the East of France”. Various encounters and books nourished his oriental fantasies and brought back that scent from his childhood. During the winter of 1884-1885, Mme Chodzko, the wife of the Orientalist, introduced Barrès to the Persian poetry of Saadi (Le Boustan, ou Verger, translated by A.-C. Barbier de Meynard, E. Leroux, 1880), before Barrès acquired Hafiz’s Quelques Odes (translated by Nicolas, E. Leroux, 1898), Jalalu’ddin Rumi’s Selected poems from the Divani Shamsi Tabriz (translated by Reynold Nicholson, Cambridge University Press, 1898) or Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat (translated by F. Henry, J. Maisonneuve, 1903). Art also developed his imagery: Persian miniatures, bought at the sale of the Raffy collection at Drouot in 1906, or the Orientalist canvases, seen at the Grand Palais in 1913 or 1914. To this poetic Orient of dreams, backed up by the Armenian Garabed Bey and Anna de Noailles, with its indeterminate geography, could be added the Orient of travel.

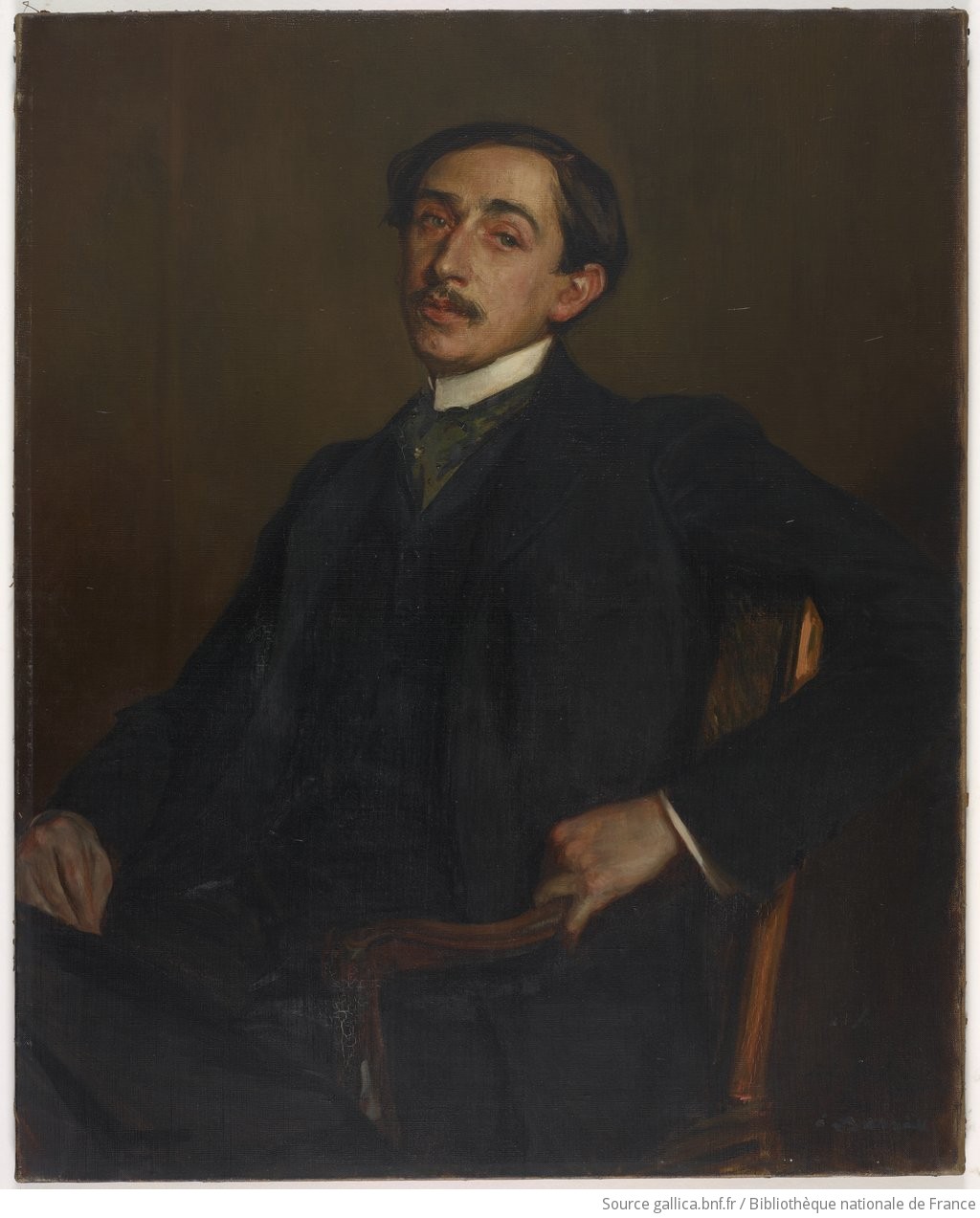

Maurice Barrès par Jacques-Emile Blanche. 1890

From 1st May to 2nd July 1914, Barrès, then aged 52, undertook his greatest journey in the Middle East. His aim was to investigate religions, from Alexandria to Constantinople, via Lebanon, Syria and Turkey, a journey that can be followed in his annotated Baedeker Guide. Just a few years after the law announcing the Separation of the Church and the State, this deputy went to see the French religious congregations to examine their condition. In the album of photographs, sent to him by Victor Chapotot, his travelling companion, he can be seen to visit, in Alexandria, Sainte-Catherine et Saint-François-Xavier high schools, the Miséricorde boarding school, and the Asile Saint-Joseph. Despite his interest in Eastern Christians, Barrès did not go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land; instead he undertook a personal investigation of the oriental mystique and dialogued with religious leaders of various faith groups: the Nizari in the castles of Alamut, Masyaf and Kadmos, and the Dervishes in Konia being this traveller’s most predictable encounters. In a letter dated 12th February 1914, and conserved in the Barrès archive of the BnF, René Dussaud gave Barrès a list of oriental books which would help him conduct this second investigation: Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy’s Exposé de la religion des Druzes tiré des livres religieux de cette secte (Imprimerie royale, 1838), Stanislas Guyard’s Fragments relatifs à la doctrine des Ismaélîs(Imprimerie nationale, 1874, from vol. XXII), René Dussaud’s Histoire et religion des Nosairîs (E. Bouillon, 1900); Voyage en Syrie, octobre-novembre 1895, notes archéologiques (E. Leroux, 1896); Clément Huart’s “La Poésie religieuse des Nosaïris”(Journal Asiatique, t. XIV, 7th series, August-September 1879); and M.-C. Defrémery’s “Nouvelles recherches sur les Ismaéliens ou Bathiniens de Syrie, plus connus sous le nom d’Assassins, et plus principalement sur leur rapport avec les états chrétiens d’Orient” (Journal asiatique, January 1855, vol. V, 5th series). Barrès took home from his journey nineteen notebooks and a large number of documents which formed the initial dossier behind Une enquête aux pays du Levant. On his return, just one article about the French congregations was published: “La leçon d’un Voyage en Orient”. The writer had then to suspend his literary project “Journal de Voyage en Orient”, meant for L’Illustration, so as to support the war effort in L’Écho de Paris.

In the post-war context, marked by the issue of the French protectorate of Syria, Barrès resumed his literary project, while doubling it: first, he wrote Un jardin sur l’Oronte, an oriental tale, “a book of desires, dreams and colours”, a “blue bird”. In it, the writer, in a style seeped in Persian poetry, told a love story between a young Crusader, Sir Guillaume, and Oriante, the favourite of Emir Qalaat el-Abidîn, in Syria. The book was serialised in the Revue des Deux Mondes in April 1922 (1st and 2nd parts) before being published in book form by Plon-Nourrit. For Barrès it led to a violent quarrel with Catholics, who accused him of having offended religion. The BnF conserves an illustrated edition with 17 watercolours by André Suréda, engraved in wood by Robert Dill (Javal and Bourdeaux, 1927). In 1932, Franc-Nohain used the novel as the basis of an opera in eight tableaux, with a score by A. Bachelet: several models of the sets, produced by René Piot, can be consulted at the BnF, on the site of the Opera Museum library. After Un jardin sur l’Oronte, Barrès wrote an account of his journey, Une enquête aux pays du Levant (Plon-Nourrit, 1923), which he dedicated to Henri Bremond, the historian of religious feeling. By retracing this twofold religious investigation, he aspired to symbolising the dialogue between the East and the West, in the tradition of Goethe’s Divan. He also presented his book as a testimony, to back up a campaign in favour of the French congregations, which he was also conducting: in 1923, for the Commission des Affaires Étrangères, he drafted reports on five missionary congregations, republished in Faut-il autoriser les Congrégations ? (Plon-Nourrit, 1923-1924).

According to Thibaudet, who discovered Une enquête aux pays du Levant after hearing of its author’s death, one consequence of the war was to place Barrès at the end of the line of romantic travellers: “After Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Gautier, and Gérard de Nerval, Barrès’s journey was the last of the romantic journeys to the Orient, or journeys to a romantic Orient. Here, too, 1914 marks a great division. Such an Orient no longer exists.” For Barrès, the fantasy of an oriental garden lingered after the war, as a source of inner energy: “Each of us, from the most humble, according to their ability, invents some paradisiac flowerbed whither to flee from the disgusting sadness of his heart, and the irritation of his mind; we emerge from such daydreams, as from sleep, recharged with strength”.

Maurice Barrès’s library has been conserved in a special archive at the BnF: Z-BARRES.