At the heart of the Arab world, the Machreq, or “Orient” – a geographical space covering Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq – was the region where Christianity was born and where it first expanded. The churches of the Near East have retained not just their liturgical but also the theological diversity of their origins.

Early Christianity was full of varied sensitivities, which were themselves the heirs of the heterogeneous nature of Judaism, in which the new faith took root. In the 4th century, the institutionalisation of churches, within the context of the Roman Empire, allowed for the emergence of an orthodoxy that was defined at the Council of Nicaea (325), but without eradicating a hardening of theological discourses. As Christianity gradually became the state religion (a status that it acquired in the East as early as 380, with the ascent to power of the Nicaean Emperor Theodosius), this initial diversity led to schisms. After the Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), theological schools that had developed divergent Christologies gave birth to what were now opposing families. The hazards of future history, with in particular western interference, heightened these divisions. We can thus distinguish:

- “Chalcedonian” churches, also called “Melkite” (from the Syriac malko, “king”, because they remained faithful to Byzantine emperor), which confessed the Chalcedon belief in the duality of nature and the unity of Christ as a person, son of God, the saviour born of the Virgin Mary, venerated in this respect as the “Mother of God”. A majority presence in Syria-Palestine (patriarchies of Antioch and Jerusalem), the Melkites became a small minority in Egypt (patriarchy of Alexandria). In the 11th century, these churches were drawn by Constantinople into the schism which, in 1054, led to the break with Rome. Having gradually adopted the Byzantine liturgy, they became part of what was now called the “orthodox” churches.

- The churches previously called “Monophysite” (the Copts in Egypt, Ethiopians, Armenians and Syriacs) were heirs of an anthropology according to which the unity of the person of Jesus was so perfect that, after his incarnation, a human and divine nature could not be spoken of, but only a single nature (in Greek: mone-physis) as divine-cum-human.

- The “Nestorian” church (so-called because it remained faithful to the memory of Nestorius, the patriarch of Constantinople, condemned at Ephesus) which has also been called, since the 19th century, the “Assyrian” Church of Christians in Iraq and Iran, came from the School of Antioch, which focused on affirming the humanity and divinity of Jesus, while neither confusing them, nor dissociating them. The term “Mother of God”, as attributed to Mary, seems to have opened the door to a sort of occultation of Jesus’s humanity.

- As of the 16th century, the Eastern Catholic Churches were born from the rallying to Rome of the faithful who were neither Chalcedonic nor Melkite: this led to the constitution of “Uniate” churches: Coptic Catholic, Syrian (or Syriac) Catholic, Chaldean Catholic (coming from the Nestorian Church), Armenian Catholic, Melkite Catholic (which kept the name “Melkite”, which had been abandoned by its “orthodox” mother church). They then experienced more or less pronounced liturgical or theological Latin influences. A special case can be seen in the Maronite Church (Lebanon, Syria, Cyprus), which claims to have always been united with Rome, but without having become detached from “Orthodox” Christianity.

- Rome also established in the Near East “Latin” communities during the period of the Crusades. This movement reaffirmed itself in the 19th century, under the Latin patriarchy of Jerusalem (1847).

- At the same time, in opposition, various Protestant or Anglican communities were created in practically all the countries in the region.

At the time of the Arab conquest, in the 7th century, Christians accounted for almost the entire population of the Near East. Their divisions increased the speed with which the conquerors took over. However, this did not lead to the rapid Islamisation or Arabisation of these lands. For a long time, the local populations remained mostly Christian and continued to speak their ancestral languages (Coptic in Egypt, the various versions of Aramaic in the Syrian-Mesopotamian area). Nevertheless, they also adopted Arabic in the 10th century, which gave birth to a specific Arab Christian literature. Before long, Arabic finally found its place in the liturgy. This process of Arabisation led to the disappearance of the older languages, or else reduced them to relics. Thus, it was quite naturally that, given the specific questions that had been raised by the dialogue with Islam, there arose an “Arabic” Christian theology with its own nuances. Christians were in the front line of all the struggles against the Arabs: the nahda, or renaissance of the Arabic cultural identity in the Ottoman Empire, the struggle against Western colonialism, political Arabism, opposition against the Zionist State and the defence of the rights of Palestinians, etc.

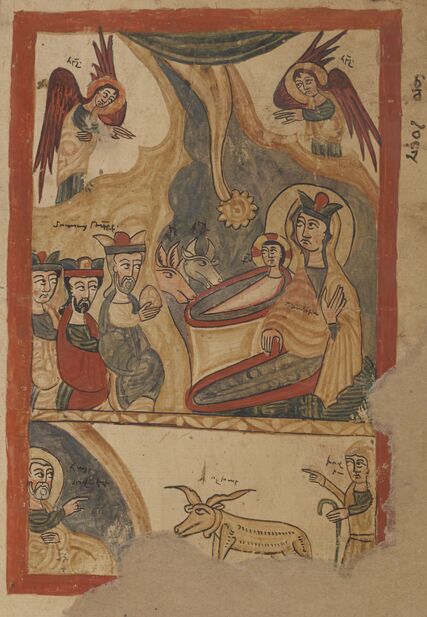

Volume de peintures illustrant la vie de Jésus, avec légendes en syriaque et en arménien. XVIe s.

It was because of political, economic, cultural and, secondarily complex religious reasons that the majority of the formerly Christian inhabitants of the Near East converted to Islam. This was a slow process, and did not lead to the total disappearance of Christianity. Traditional Muslim society allowed non-Muslims (dhimmis) to practice their religion. But of course the more Islam became predominant, the more the situation of the now minority Christians became difficult: they occasionally experienced severe discrimination and even violence, but this was sporadic. Very rarely, they were also victims of attempts at eradication. The cultural exchanges between Christians and Muslims were rich, and reached their golden age between the 9th and 13th centuries, at once in Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia.

It was above after the 14th century that the number of Christians started to decrease significantly in the Near East. A form of Muslim coercion contributed to this phenomenon, but it would be wrong to focus only on this dimension. What is more, this drop was not constant: under the Ottoman Empire, from the 16th to the beginning of the 20th centuries, the Christian communities of the Levant even experienced a demographic expansion.

When it comes to the 20th century, the proportion of Christians in the Machreq (standing at between 10 and 15% of the total Arab population in the Near East in 1900) diminished considerably, until it reached its present rate (between 6 and 8%). They are however more numerous in absolute terms (about ten million) than they were a hundred years ago (under 2 million). Their communities are also more lively and open to modernity. At the same time, they suffer from the general malaise of Arab societies, whose causes are legion: the chronic instability of the region created by the Israeli-Arab conflict, the associated impossibility of developing genuine civic democracies, or the locking-down of societies by dictatorial or predatory regimes, in part because of the rise of cause Islamism. Since the 1970s, the latter cause has heightened the feeling of precariousness experienced by Christians, who are being confronted by a socio-political project from which they are excluded. As a result, many of them have chosen exile. The mounting crises that the Arab world has experienced since the start of the third millennium and the social upsets set off by the “Arab spring”, leading above all to the break-up of Iraq and Syria, while also seriously weakening Egypt, have darkened the future perspectives of these communities.