The practice of photography for Devéria was closely linked to the documentation of excavations and the framing of his prints should be understood in this context.

Théodule Devéria was the son of the great draughtsman, illustrator and lithographer Achille Devéria (1800-1857) and the nephew of the romantic painter Eugène Devéria (1805-1865). His mother, Céleste Motte, was the daughter of the Parisian lithography printer Charles Motte. Thus, Théodule Devéria grew up in a teeming artistic milieu where Dumas and Hugo rubbed shoulders with Delacroix, Liszt and Musset. It was while listening to the tales of the Egyptologist Prisse d’Avennes, when he posed in an oriental costume for his father in 1843, that his vocation was born precociously. This vocation was then confirmed when visiting the rich collections of the Museum De Lakenhal in 1846. He was encouraged by the engraver Jules Feuquières, a friend of Auguste Mariette and collaborator with this grandfather in the publication of Champollion’s Grammaire égyptienne. The Egyptologists Charles Lenormant and Emmanuel de Rougé also supported him. At the Collège de France and the Ecole des Langues Orientales he attended the lessons of the greatest teachers, such as the Orientalist Etienne Marc Quatremère, and then in 1851 he became an employee in the collection of Stamps at the Bibliothèque impériale (the current department of Stamps and Photography of the BnF) where his father had been in charge of the collection of engravings since 1849.

In 1855, he was appointed epigraphist at the department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre. His mission was then to classify and list the huge quantity of objects coming from the excavations of the Serapeum of Memphis, discovered in 1850 by Auguste Mariette, who was then head of the French excavations in Egypt. That same year, he took part in the publication by Firmin Didot of the album of the young American photographer and Egyptologist John B. Greene (1832-1856), Fouilles exécutées à Thèbes dans l’année 1855: textes hiéroglyphiques et documents inédits, by lithographing two plates for the volume. In 1856, he began his collaboration with Mariette for the illustrations of the work Choix de monuments et de dessins découverts ou exécutés pendant le déblaiement du Sérapéum de Memphis. Finally, he accompanied Mariette to Egypt on a trip from Memphis to Karnak to photograph the excavations of the Serapeum and of the temple of Amon. After setting off on 10th December 1858, he remained there until April 1859, devoting his time to following Mariette to the various excavation sites. In January 1862, he returned to Egypt with Mariette, who continued his excavations of the Serapeum, before staying for a third time in 1865, this time in the company of Henri Péreire, M. Surell and Arthur Rhoné. During this pleasure tour, he used glass collodion plates, while previously he had used waxed paper negatives, and took more portraits and souvenir prints, glass plates allowed for a faster shooting time, thus favouring this kind of subject.

The beginnings of his photographic practice, no doubt initiated by his father, go back to 1854. He has left us a large number of reproductions of ancient engravings and drawings, but above all a huge production linked to his work with Mariette – objects, inscriptions, excavation sites in Egypt – even if he also produced a few shots in France (in particular in Courseulles in the Calvados). He struck up a friendship with the painter and photographer Paul Berthier (1822-1912) with whom he collaborated on a publication concerning the Serapeum of Memphis. It was Paul Berthier who took most of the photographs of objects from Mariette’s excavations, intended for the Louvre. The photographs of Devéria preserved at the BnF in fact come from the Berthier archive, which was donated by the photographer Paul Sauvanaud (1847-1934) in 1921. All of his papers, documentation and negatives were sold to the Louvre by his widow after his death, on the recommendation of Emmanuel de Rougé. They are all now currently in the archives of the Musée d’Orsay. The practice of photography for Devéria was closely linked to the documentation of excavation sites and the framing of his shots should be understood in this context. He also saw his prints as materials for his futures publications. His deep knowledge of the different illustration techniques, drawing, engraving, lithography and photography, as well as the artistic sensitivity which he had also inherited from his father, made him an exceptional collaborator on Mariette’s great publishing project. His death in 1871 meant that he did not see the conclusion of this enterprise which owed so much to him.

Some of his work, comparable to that of Auguste Salzmann (1824-1872) or Greene, has, in our eyes, an intrinsic beauty that transcends its initial purpose.

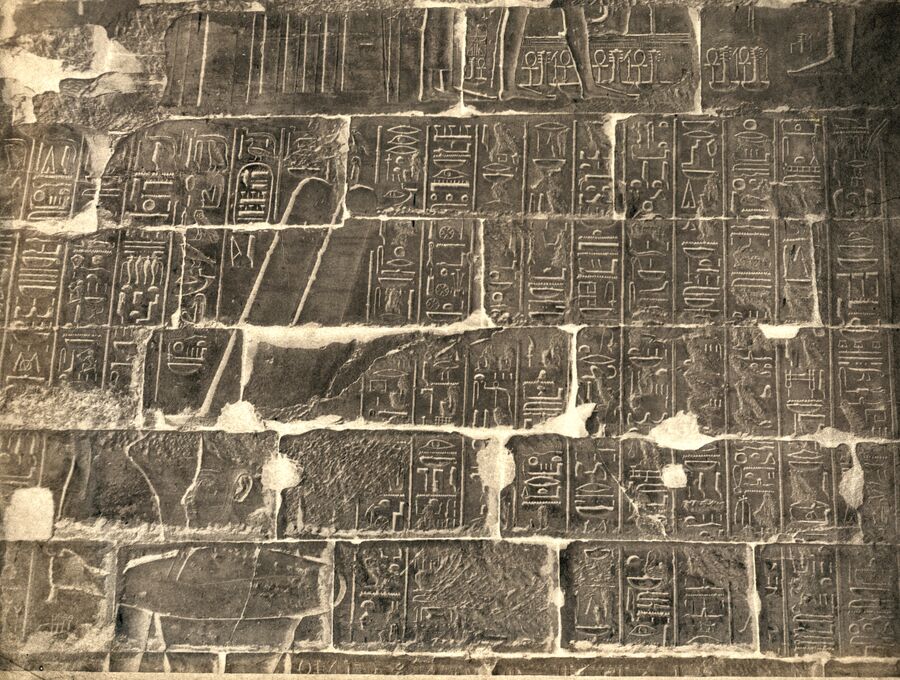

Karnak. Wall with reliefs and hieroglyphs: negative photograph. 1859