Recently rediscovered, the photographer Beniamino Facchinelli (1839-1895) took over a thousand pictures of a monumental and picturesque Cairo.

They stand out for their originality from the commercial photographs of his contemporaries, for example those of the Bonfils family or the father and son Sebah team.

Most of them were produced on the request of European enthusiasts committed to the defence of historical Cairo’s architectural and urban heritage. On the one hand, the collapse, beginning in the early 19th century, of pious foundations (Muslim and Christian endowment properties) which had traditionally guaranteed the mission of maintenance, and thus of the perpetuation, of historical buildings, and, on the other, the urban improvement projects undertaken during the 1860s, with their share of inroads, revamping, radical rebuilding and new constructions, had led to the ruin and dilapidation of many ancient edifices. A campaign of European awareness raising about the fate of Cairo’s monuments was launched at the end of the 1870s by a composite group of enthusiasts, including in its ranks the polygraph Arthur-Ali Rhoné, the architect Ambroise Baudry, the British numismatist Edward Thomas Rogers and the German architect Julius Franz, alongside the Egyptian historian Yacoub Artin and the engineer-architect Hussein Fahmy, who in 1868 had been entrusted with the construction of the al-Rifai mosque in an historicist style. This alert led to the creation in 1881 of the Comité de conservation des monuments de l’art arabe as part of the administration of endowment properties (waqf). This body was charged with making an inventory of monuments, watching over their upkeep and taking care of their restauration. A list of over 800 edifices had been drawn up by 1883; an ambitious policy of scholarly restoration of monuments developed fully in the next few decades.

For the most part taken in the 1880s, Facchinelli’s photos provide a rare and precious record of the actual state of these monuments before the first series of restorations. They document closely and without the slightest gloss the ravages the edifices had suffered from time, earthquakes, rapacious collectors and merchants, or the carelessness of guardians and entrepreneurs. They illustrate the ongoing restorations. They also provide information about the building-up of the collections of the “Musée Arabe”, founded in 1880 to house and conserve the furnishings and deco made of stone, wood or ceramics which were threatened with disappearing from these major sanctuaries. Between two commissions from his various clients, Facchinelli gave free rein to his own interest in the social life on the streets of Cairo, the movement of men and women absorbed in their everyday activities, and the presence of pets in the city. Taking advantage of the intense light of Cairo and of his familiarity with its side-streets, he sometimes produced images which are close to the instantaneous, captioning them as such. He allowed the passers-by that surged up around him to appear in the frame, intrigued as they were by the operation of taking photographs with a decentred lens, tripod and black hood. As a user of the last examples of gelatino-bromide glass plates before the arrival of the flexible negative, and keen on pictorial experiments playing on exposure times, the alternation of light and shadow, wide angles and unexpected framing, this photographer also composed, possibly inadvertently, extremely poetic shots.

This essential documentation about the construction heritage of ancient Cairo was widely used by Arthur-Ali Rhoné, Julius Franz, Henry Wallis, Max van Berchem, Henri Saladin or Gaston Migeon, in their publications about Islamic architecture, before falling into oblivion. It can now be found dispersed among French, Swiss, Italian, Finnish and British libraries, and stands as just a part of the photographer’s body of Egyptian work. Born in a territory that was part of the Habsburg Empire until 1919, committed as early as 1859 to the cause of Italian unity then, like many such partisans, becoming part of the Egyptian administration during the 1870s (he is known to have been attached to the military staff in 1880), Facchinelli also left behind portraits and journalistic reports, such as one concerning the journey that the crown prince of Italy, the future Victor-Emmanuel III, made to the Middle East in 1887. It was also possible to obtain from his studio, situated on the edge of the old town, touristic views of Egypt.

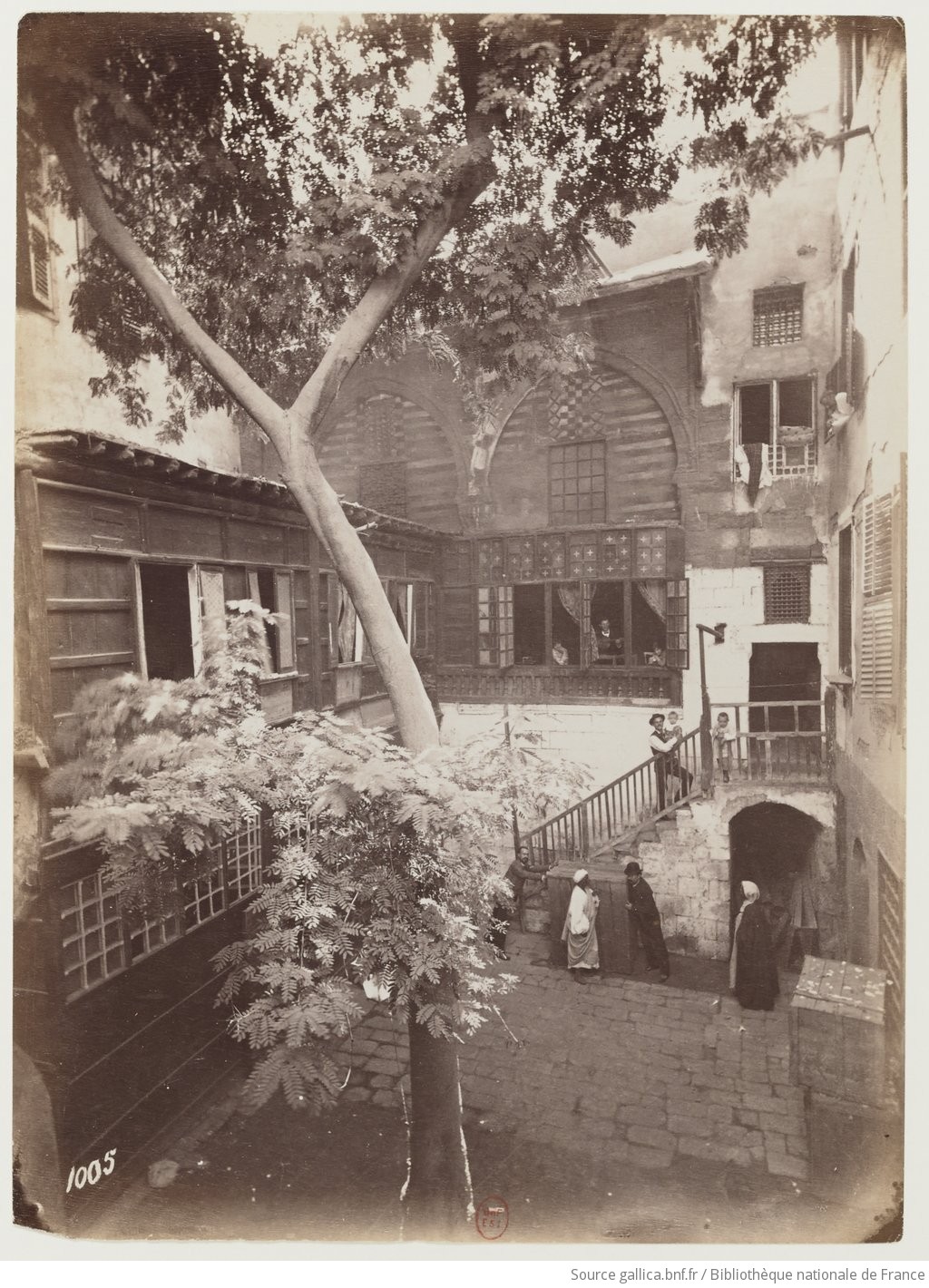

Corte Casa presso Hotel du Nil. Facchinelli’s house, he is depicted on the stairs with his children. 1873-1895