King François I of France entrusted Jacques Cartier with three Atlantic voyages (1534-1542), hoping to contest the Spanish naval monopoly and find a new route to the riches of Asia. Although Cartier failed to find spices and gold, the man from Saint-Malo kindled French ambition to explore North America.

An Iberian World?

When Juan Sebastián Elcano returned to Seville in 1522, completing the circumnavigation begun by Magellan three years earlier, he added another imaginary line to the surface of the globe, which can be seen in the portolan atlas made by the Genoese chartmaker Battista Agnese in 1543. It was a Spanish line, a challenge to the other line (1,600 km west of the islands of Cape Verde) drawn by the Iberian powers in the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which divided the world into two zones: Spanish territory to the west of the line, Portuguese to the east. This arrangement can be seen particularly clearly on the Cantino planisphere of 1502. With one simple line, Spanish and Portuguese colors flew over each half of the world.

A few dates further show the strength of these two kingdoms. Their power over the Old World and their appetite for the New began to grow from the moment Columbus reached the Americas in 1492 in the service of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. In 1521, the Aztec empire was conquered by Cortés; in 1533, the Incan empire likewise fell to Pizzaro. In their place rose a New Spain (1535) and a New Castile (1529). Meanwhile, in Europe, the armies of the Spanish King and Emperor, Charles V, drove the French out of the Duchy of Milan, besieged the Pope, and pillaged Rome, making Italy the land of a future pax hispanica.

It is only in the shadow of this Iberian chronology and geography that the voyages of Jacques Cartier can be understood.

The Disputed Inheritance of Adam

In January 1541, noting half-jokingly that “the sun [shone] for him just as much as it did for others,” François I approached the Grand Commander of Alcantara to contest Iberian pretensions to global expansion, asking to see him “to learn how he had divided the world.” The world, after all, belonged to all descendants of the Biblical Adam, and certainly to the French as much as to the Iberians. François I did not even wait for an answer before sending an expedition, commanded by Verrazano, to explore the eastern coasts of North America in 1524. Ten years later, the King decided to outfit another expedition under the direction of Captain Jacques Cartier, hoping to find a northern and western sea route to the riches of the Asia-Pacific World.

Cartier’s Voyages

In addition to finding a trade route, the voyage also aimed to consolidate French claims to these new American lands. French ambitions – so far expressed only cartographically, with the first Nova Gallia marked on a 1529 map by Girolamo da Verrazano, brother of the Florentine explorer – had already been thwarted in 1525-26 by Estéban Gomez and above all Vasquez de Ayllon, who founded the colony of San Miguel de Gualdape in “French” territory to the north of Florida.

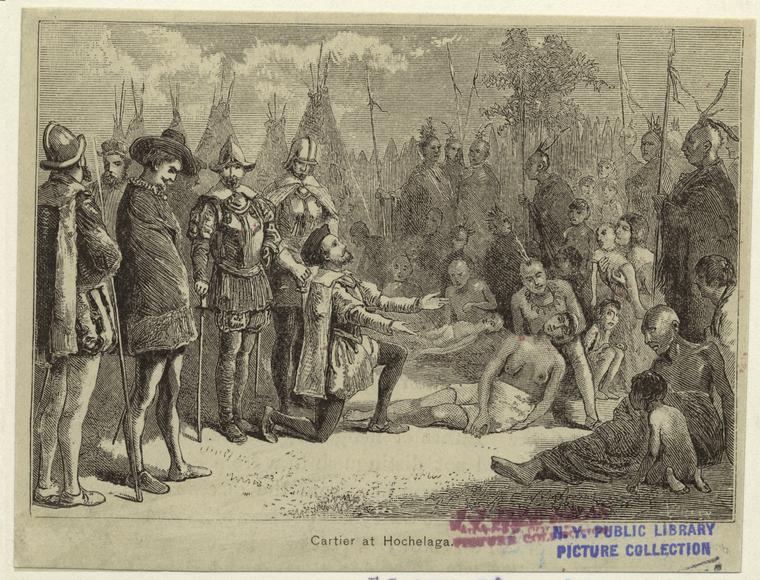

During his three voyages (1534, 1535-1536 and 1541-1542) Cartier explored the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River and sailed upriver past Stadacona (the future Quebec City) and the Iroquoian village of Hochelaga (the future Montreal) before his advance was thwarted by what would become known as the Lachine Rapids. The first two expeditions fell short of their expected goal – finding a “Northwest Passage” to Asia – but Cartier’s perseverance (not to mention the stories he and Domagaya and Taignoagny, two sons of Stadacona’s leader, told the King in person) convinced François I to pursue these initial efforts. He would authorize a further voyage, this time intended to found a colony, establish trade with the mythical kingdom of Saguenay (much extolled by his informers), and promote Christianity as required by the Church.

Cartier in the New World

In August 1541, Cartier, serving under La Rocque de Roberval as pilot of the expedition, founded the settlement of Charlesbourg-Royal at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Cap-Rouge Rivers, near Stadacona. This initial establishment was a failure, but the next summer, Roberval tried again, establishing the fort of France-Roy on the same site.

However, success once again turned to failure, culminating in the final departure of the French in September 1543. It was as disappointing as Cartier’s return to France a year earlier, his ship carrying nothing but valueless stones. Although the Canadian experience from 1534 to 1543 did not produce lasting colonies or discover valuable resources, it did set a pattern of a transatlantic French initiatives as audacious displays of royal ambition, displays that were only interrupted by the French Wars of Religion and that recommenced immediately after the peace treaties of 1598.

Published in may 2021

.png)

.png)