The word “Palestine”, coming from Greco-Roman antiquity, gradually fell into disuse in Arabic after the Islamic conquest of the 7th century, but without ever completely disappearing.

The region quickly became a holy land for the Muslims, with Jerusalem thus being called “sacred” (al-Quds). The crusades accentuated this phenomenon of Islamic sacralisation and, after the re-conquest, the Muslims of the region were given the specific mission of defending the holy land against the ambitions of the “Franks” (Europeans Christians).

In the 19th century, Europeanns reintroduced the use of the term “Palestine” in the context of conflicts about Christian holy places, which caused the Crimean War. The Ottoman administration set up the administrative division of the sanjak in Jerusalem, which depended directly from the Empire’s capital. The holy city thus became the administrative centre of a which was, at the beginning of the 20th century, called Palestine in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. The creation of a specific regional identity was based on the same model as the Syrian and Lebanese identities. Because they were not supported by a state apparatus, these identities had hazy contours and were presented as being both complementary and possibly opposed to a newly emerging Arab political identity.

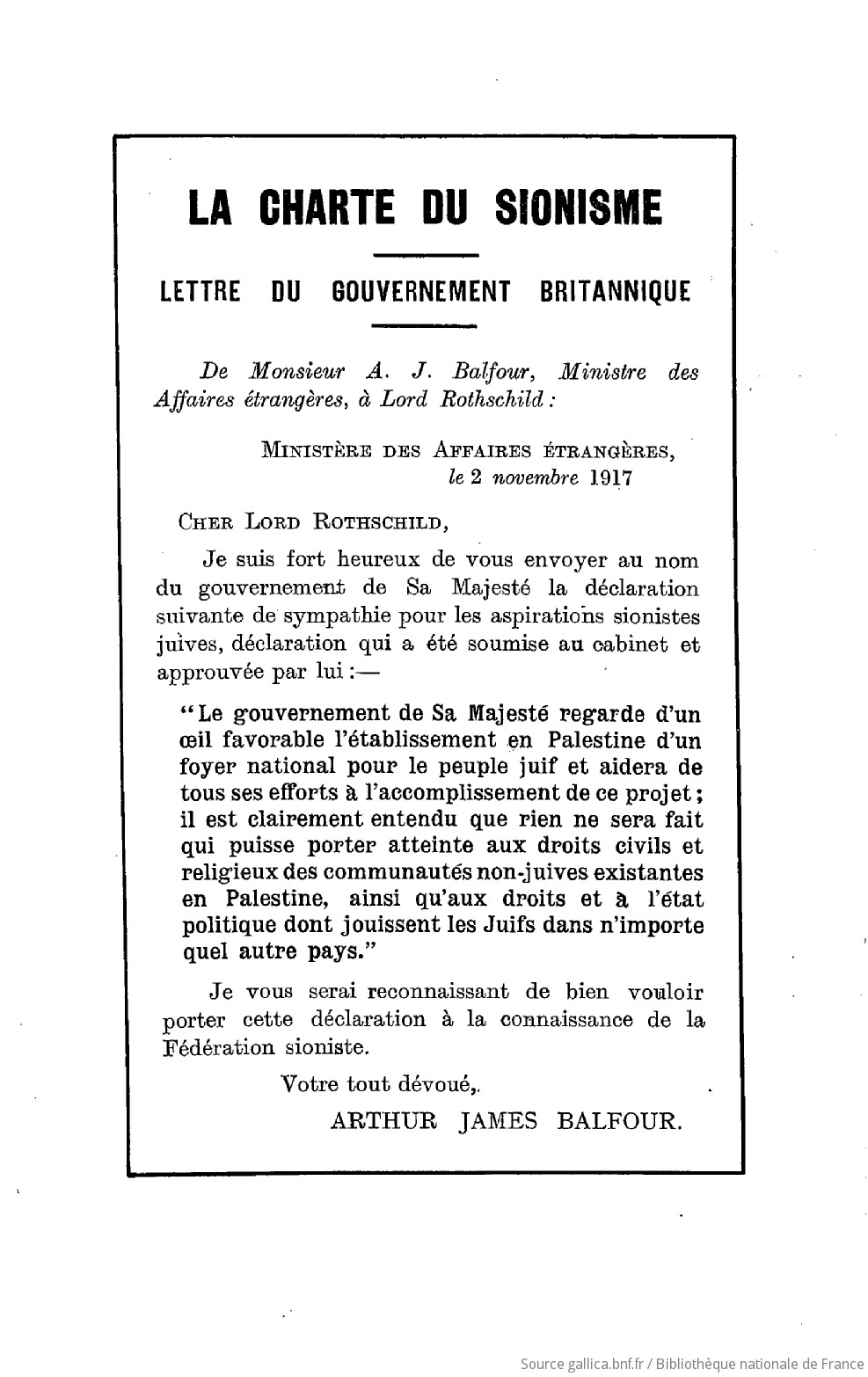

The development of the Zionist movement at the same time was seen as being a danger by the inhabitants, who saw it as announcing their expulsion from their lands and homes. The Balfour declaration of 2nd November 1917 heightened this phenomenon by creating a distinction between the Palestinians and other Arabs. The clause maintaining their “civils and religious rights” was rightly seen as defining them as foreigners in their own country, hence their contestation of the British mandate.

La Grande-Bretagne, la Palestine et les Juifs. Le Peuple juif célèbre sa Charte nationale

This “Mandatory Palestine” included the former sanjak of Jerusalem, as well as two other former Ottoman districts that used to be part of the Ottoman province of Beirut. It was in this new territorial context that Palestinian nationalism was born.

The political identity that was adopted was “Palestinian Arabs” and not “Southern Syrians”. This was at once analogous to uses in the neighbouring countries (where there was talk of “Syrian Arabs”) and specifically in the Mandate, because they were also termed “Palestinian Jews”. But the Zionist movement refused to use the word “Palestine” in Hebrew texts, where it was replaced by “land of Israel”. It was thus impossible to bring out a Palestinian identity that was shared between the two communities.

Thus, the British found themselves faced by the impossibility to reconcile their obligations towards the Jews and the Palestinian Arabs. Violence emerged either around conflicts about the Holy Places, as in 1929, or around the colonisation of the territories (1936-1940). The Palestinian revolt was harshly crushed by the British, while also limiting drastically Jewish emigration in 1939.

This conflict ended up as a zero-sum game in which the advance of one side could only be made to the detriment of the other. Each of them wanted the State for themselves, committing themselves only to recognising the specific rights on the side that was to become the minority.

Just after the Second World War, the Arab-Palestinian economy was particularly flourishing and the economic relationship between the Jews and Arabs settled at 60/40%. There was a greater possibility for the extension of the Jewish national presence, which made it all the more urgent for the Zionists to set up a Jewish state, which was the only way of being able to take control of the territory with a view to its development. At the time, the Arab population stood at two thirds of the total population, but with a large proportion of children, whereas the Jewish population had a far greater percentage of young adults.

The Palestine Partition Plan that was voted by the United Nations’ General Assembly on 29th November 1947 was made to the detriment of Palestinian Arabs, despite the guarantees on offer. It was all the more inapplicable because it was impossible to establish any trust between the two sides. Violence thus broke out on 30th November 1947.

The conditions of the exodus were open for discussion given the large number of situations created by times and places. But, right from the start, there was a policy to forbid returns, decided at the highest level of the state of Israel retours with a view to make acquisitions permanent. This forced diaspora forced created the current Palestinian national movement.